There is a romantic tradition in American popular culture of the itinerant adventurer. A man alone, traveling around the country, meeting people, becoming involved in their lives for a short time, then wandering off again. It’s a common television/movie trope; we’ve seen protagonists travel by horse (Have Gun, Will Travel), by car (Route 66), by motorcycle (Easy Rider), on foot (Kung Fu).

Alec Soth would be an unlikely television or movie protagonist, but he has this in common with them: he travels around, encounters strangers, involves himself in their lives long enough to take their photograph, then wanders off again. Soth travels with a camera. A big camera. An 8×10 view camera. Taking a photo with a large format camera is a time-consuming process. That process takes long enough for Soth to actually interact with his subjects. From these experiences, he’s managed to build a career and produce two major photographic projects. I’m absolutely certain he’ll produce many more.

Soth was born and raised in Minnesota. He describes his childhood home as “a neighborhood that wasn’t quite a suburb and wasn’t quite a city,” surrounded by fields and woods. He was apparently a shy, introverted, socially awkward child. He attended Sarah Lawrence College with the intent of becoming an artist; his first interest was in painting, then later in sculpture. He began taking photographs of his sculpture, became somewhat interested in photography, then attended a lecture by photographer Joel Sternfeld.

“In one slide he pointed out his van, the van he had used to traverse America. Something clicked. I realized that was what I wanted to do. This sort of boyish wanderlust is common in America, but it was new to me.”

Soth’s first major project, Sleeping by the Mississippi, is a classic wanderer’s tale. He’d been photographing the river for some time because it ran directly through his hometown. He began to think of the river itself as a sort of metaphor for wandering. “This is a huge part of the mythology of the river,” Soth says, “Huck Finn and all of that.” So he wandered up and down the river, photographing the people and places he encountered. He discovered the river, which was once a primary driver of the American economy, had become “a worn and faded place. But [the people who] remain often make really creative and peculiar lives for themselves.”

That project was a major success; it led Magnum to recruit Soth as a member. The influence of the Magnum agency led Soth to take a more deliberately documentary approach to his next project, Niagara. For this salon, I’m going to focus on Niagara.

The small town of Niagara Falls, of course, is best known for the dramatic waterfalls of the Niagara River. With the introduction of steam trains in the early 1800s, the town became a popular marriage and honeymoon destination. The falls have also drawn risk-takers. In 1901, a 63-year-old widowed schoolteacher named Annie Edson Taylor, hoping to become famous, strapped herself into a custom-made wooden pickle barrel and rode it over the falls. She survived., but her stunt sparked a series of glory-seekers and desperate suicides that have continued to this day.

Soth had never visited the town; he chose it as the subject for his project based entirely on the town’s reputation as the honeymoon capitol of the US.

“I thought of the project as being like a love song–a sad love song–and sort of emotional, hitting on certain cliches, but hopefully being moving in a way.”

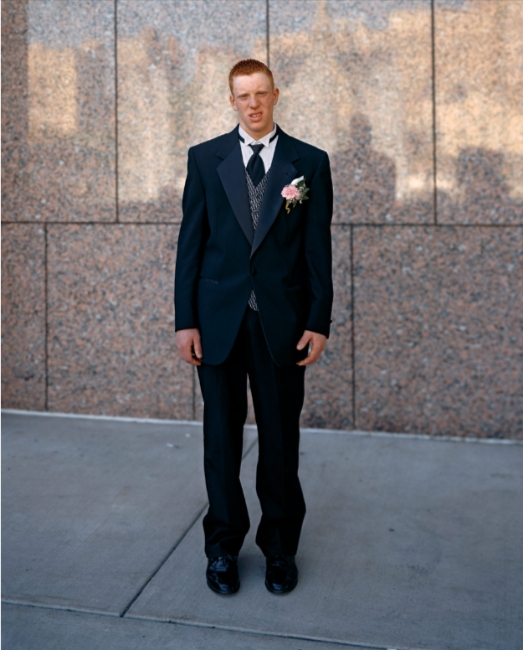

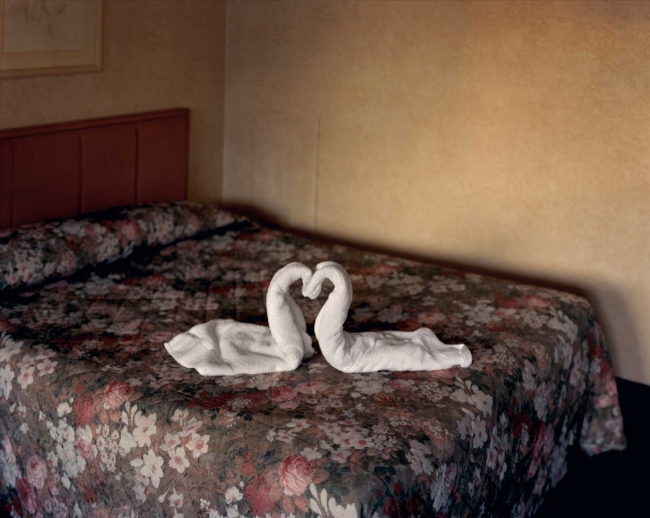

Beginning in 2004, Soth made seven trips to Niagara Falls, each lasting two to three weeks. This project has an unfussy documentary style that is somehow both melancholy and hopeful. The images seem divided into three categories: portraits, motelscapes, and the waterfalls themselves. The combination of the three creates a poignant whole.

The subjects of the portraits seem precariously balanced between optimism and reality. They clearly have hope for a happy future, but also seem resigned to a future that’s mostly just a long continuation of their current circumstance. There’s something brave about them, something courageous, even heroic. They’ve put themselves into the emotional equivalent of a barrel going over the falls. In his own way, Soth appears to find them heroic as well. The portraits aren’t flattering, but there is a lyrical tenderness to them that is heart-rending.

That tenderness is at odds with the reality of the town of Niagara Falls, which suffered an economic collapse in the 1960s. Soth was surprised by the depressed economy and the general cheeziness that had overtaken the community. His early perception of the community quickly took on a darker edge. His images of the cheap motels reveal the contrast between the romantic dream and the gritty reality. Soth even photographed the love letters left behind in the motels, and the farewell letters of those who apparently changed their minds at the last moment. One such letter ends with this: “If there was a nice apartment and I have a decent job and you felt happy and thought there could be a nice history together, would you come home?“

And always, in the background, are the waterfalls themselves–the force of nature that is the source of the mythology of Niagara. They are astonishingly beautiful, and Soth’s photographs reveal their intense both their magnetic allure and their awesome power. Soth says,

“There’s a force there that calls people to it, and I do think the power of passion or new love is sort of reminiscent of that. I just think that sort of passion or new love crashes down eventually. That’s what I was interested in: passion and its aftermath.”

It’s not surprising that so many young people with such a huge capacity for hope and so little real reason on which to base it flock to Niagara Falls. It’s not surprising that people are always willing to climb into the barrel and trust their luck going over the falls.

It probably shouldn’t be a surprise that sometimes people get lucky and everything goes just right.