The first time I heard the name Judith Joy Ross it was in connection to portraits of members of the United States Congress. It’s hard to imagine a less interesting photo series (at least that was my perspective), so I pretty much ignored her. Until I came across this photograph.

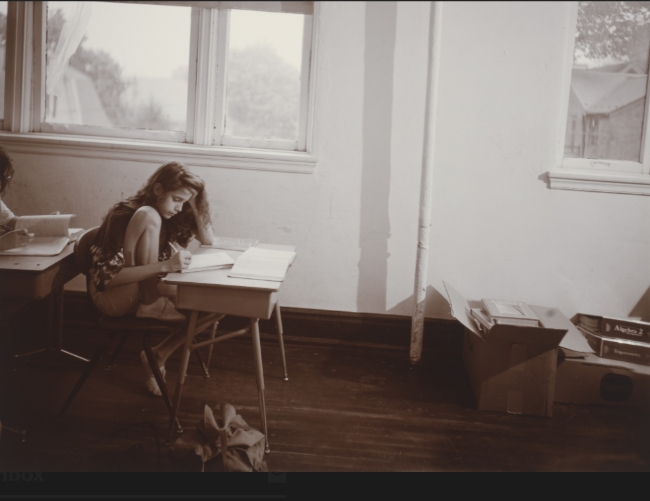

There’s something so vulnerable–not just vulnerable, but openly vulnerable–that makes the portrait compelling. You can sense the uncertainty of these young women, the question they must be silently asking. Why do you want to take our photograph? There’s nothing special about us. Why us? And you can almost sense the photographer’s answer. Because you ARE special, even if you don’t recognize it.

“I basically think people want to be recognized and appreciated. When you put a big camera in front of them, they think, ‘I must be interesting.'”

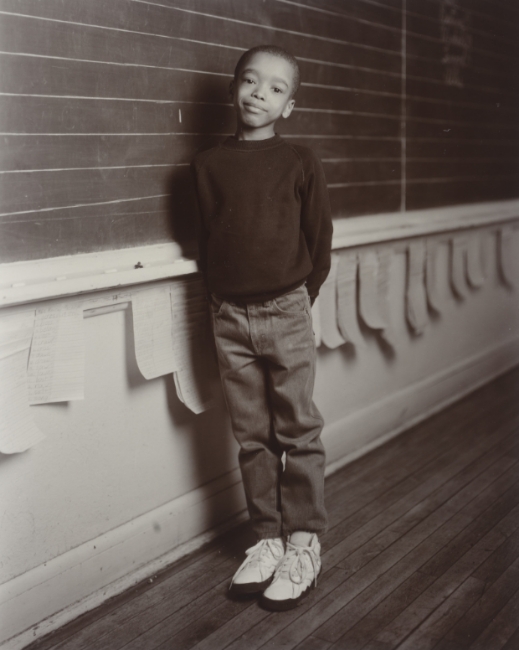

Judith Joy Ross is a fine arts portrait photographer. Throughout her career, she’s focused her 8×10 view camera on both common people in common places (a swimming hole in rural PA, visitors to the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington, DC, troops getting ready to ship off to war) as well as on the policy-makers whose decisions affect the lives of common people (members of US Congress). But she’s perhaps best known for her Hazleton Public School portrait series, which is the focus of this Salon.

Ross grew up in Pennsylvania’s coal country; her father owned a five-and-dime store in Nanticoke. In the late 1950s and 1960s, she went to school in the same public school buildings her mother attended in the late 1920s. In the 1990s, she returned to the same school system to photograph the students. Of these portraits Ross has said, “I feel like these pictures are my childhood. This isn’t me, but it is me.”

There is a directness and a lack of irony in the way Ross creates these portraits. Much of the power of the photographs comes from the subject’s unstudied innocence, from their physical and social awkwardness, from their absence of sophistication. There’s a sort of honesty and integrity in the simplicity of the portraits.

Some of that is a result of the camera. An 8×10 view camera is big. It’s impressive. It’s a very serious-looking piece of photographic technology. And yet, because it also seems old-fashioned and quaint, it’s not intimidating. Ross says,

“[The big 8×10] camera is vital. I use it like a charm, like an attractant. I would not enjoy pointing a camera to a stranger. I would feel like I am doing something to them. With a view camera, we are doing something together.”

But it’s also the way Ross works. She cultivates her subjects’ desire to be interesting. It’s on the verge of being manipulative, except that Ross is apparently absolutely sincere. That genuine sincerity lasts as long as it takes to get the photo. Ross said she didn’t get to know the students personally and hasn’t kept in touch with them. She has no idea if they’ve ever seen their portraits.

“This is the way I work. I’m in love with you intensely, and [then] I don’t ever have to see you again. I’m not big on intimacy, except in a visual way.”

That strange combination of intimacy and emotional distance gives the portraits an old-fashioned feel. That feeling is reinforced by the arcane process she uses to print her images. Ross sandwiches the large negative with printing-out paper, which she then exposes to sunlight for a few minutes to a few hours. Afterwards, she tones the prints in a process that produces shades of brown or grays that are tinged with purple. No two prints are ever quite the same.

In the end, it’s the directness and simplicity of portraiture that drives Judith Joy Ross. You stand there, she takes your photograph, something about you and your life is revealed…and that’s enough. “A good story in a picture is much better than being alive,” according to Ross. “Being alive is complicated and hard, but a good picture — I can get lost in it.”