Los Angeles-based photographer Richard Renaldi is leading the life so many amateur photographers would like to live. He travels widely, he photographs the things and people he finds interesting, and the resulting prints (which sell for thousands of dollars) are hung in museums and art galleries.

Renaldi was born in Chicago in 1968, earned a BFA in photography from New York University in 1990, and moved to Los Angeles in 2003. He then spent a few years sporadically hauling a large format camera around the West and the Great Plains.

My impression is that Renaldi is often involved in several projects at the same time, rather than focusing on a single topic and then moving on to the next. It may be that he doesn’t actually perceive them as projects–that he’s just shooting photographs that interest him–and later he finds commonalities among them that allows him to present them as projects. He’s photographed such diverse subjects as the lobbies of corporations, long-term HIV survivors, people in bus depots, elderly gay/lesbian couples, fathers and son portraits.

Each of these projects is fascinating in its own way. But I’m most attracted to his exploration of the Great Plains, that vast stretch of North American prairie land between the Missouri River and the Rocky Mountains. That area has a strange history.

In mid-1800s the US government, for a variety of political and social reasons, wanted to encourage the settlement of the area west of the Missouri River. The result was the Homestead Act of 1862. It gave to any citizen (or anybody who had filed to become a citizen) 160 acres of undeveloped land, free of charge. All the person had to do was live on the land for five years and build a house of at least 12 by 14 feet. By the time the act was repealed, more than 270 million acres–nearly 10% of the area of the United States–had been claimed and settled. Around two million people moved to the area.

The population of the Great Plains rose radically, stabilized for several decades, then began to gradually decline. In the last few decades, however, the rate of decline has escalated rapidly. Family farms are being replaced by giant agri-business conglomerates. Extended periods of drought have crippled farmers and ranchers. Employment opportunities have dwindled. The consequence has been for the young people to leave and never return.

“I find these towns both beautiful and sad. There is not much to do for the youth in these places and the ones that remain are mysterious to me.”

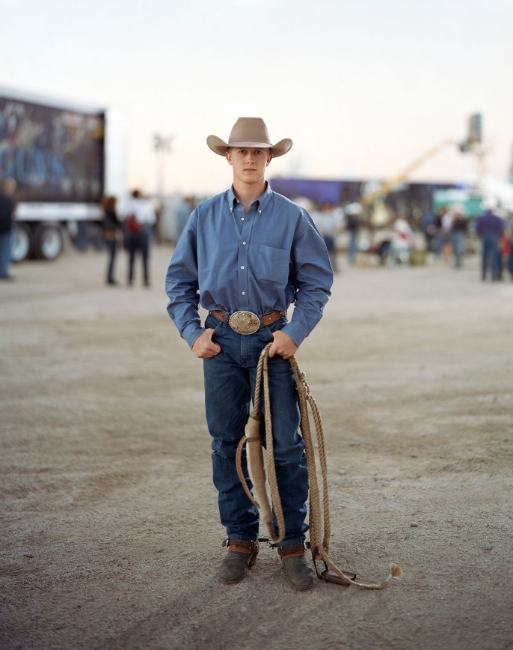

Renaldi wandered the Great Plains photographing the landscape and the small towns. More importantly, he photographed the people who live there. He’s described the work as being in the tradition of August Sander (who, you’ll recall from an earlier Sunday Salon, also traveled his homeland photographing workers in their natural environment).

“I like the idea of stopping and looking at someone and them looking back — almost, if you will, “the stare”. The 8 x 10 lends itself to those expressions as well since it is not a rapid process.”

There is a refreshing lack of irony in Renaldi’s portraits of the people of the Great Plains. There is sentiment, yes, and emotion, but none of the urban cynicism we often see in modern portraiture. And yet Renaldi’s camera also records the influences of our media-saturated planet. Even the most white-bread of small town farmboys on their BMX bikes are subject to the gravitational pull of urban culture. In some secret place, this kid probably imagines himself to be the ‘gangsta’ of Havre, Montana (population 9,621).

It’s not just the towns that are both beautiful and sad. So are the people. Especially the young, because the Great Plains is bleeding young people. The median age of the population in the majority of counties in the plains states is now in the 50s.

It’s impossible to look at the face in the photograph below and not feel compassion. This young woman is uncertain–uncertain about her life, uncertain about her future, uncertain about herself, uncertain why anybody would want to take her photograph. She doesn’t understand that what she represents is beautiful. She doesn’t understand that she is beautiful.

There is something ineffably sad–and yet somehow perfectly appropriate–that a gay man from Los Angeles sees the beauty that so many would overlook in a place where nobody goes.