Anne Brigman was to photography what Isadora Duncan was to dance. She was a free spirit long before the phrase “free spirit” became a cliché. She was born in Hawaii, moved to California at age 16, married a sea captain at 25, and built a photographic career by photographing herself, her sister, and her friends in the nude in settings of spectacular natural beauty. And she did all that a century ago. She was born in 1869.

When Brigman began to study photography, she was on the wrong coast of the wrong continent. In 1902 the world of photography was centered in Europe, although there was a dedicated group of practitioners on the Northeast coast of the United States. Yet within just a few years, she had been invited to join what was then the most exclusive conclave of American photographers — Alfred Stieglitz’s Photo-Secession movement. The purpose of the Photo-Secession movement was to compel the art world to see photography as “a distinctive medium of individual expression” equal to the traditional art forms of the time. Anne Brigman was the only photographer west of the Mississippi River to receive such an invitation; she was also the only woman.

Brigman’s earliest photographs were decidedly in the pictorialist tradition…photographs that emulated the style of painting. After shooting the photographs she did extensive post-processing, using pencil and paint to alter and enhance the image.

Brigman is best known for her photographs taken in California’s Sierra Nevada mountains. In the early 1900s, this mountain range was still relatively remote and inaccessible. Brigman would hike up into the mountains, sometimes alone and sometimes with friends, toting a seven pound 4×5 camera, a heavy wooden tripod, a number of photographic plates, as well as supplies and gear for an extensive stay — anywhere from two weeks to two months. Photography required a serious amount of dedication in those days.

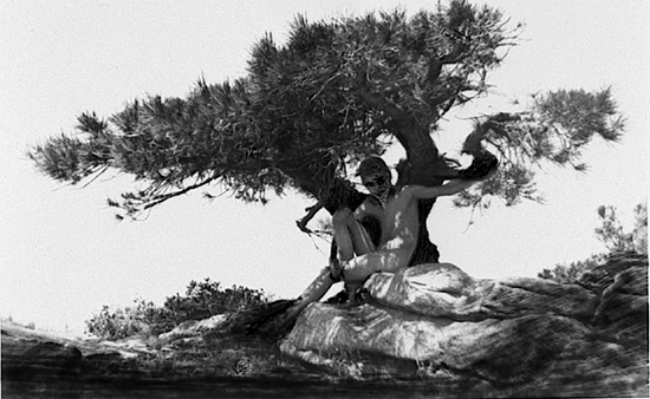

She visited the Sierras often enough that she developed what she called ‘friendships’ with individual trees and peaks. In 1926, after she’d become an established photographer, Brigman wrote an article for Camera Craft magazine in which she described her relationship with one such tree.

“One day on one of my wanderings I found a juniper — the most wonderful juniper that I’ve met in my eighteen years of friendship among them…. It was a great character like the Man of Gallilee or Moses the Law-giver, or the Lord Buddha, or Abraham Lincoln…. Storm and stress well borne made it strong and beautiful. I climbed into it. Here was the perfect place for a figure; here the place for the right arm to rest, and even though my feet were made clumsy by boots, I could see and feel where the feet would fit perfectly into the cleft that went to its base.”

Brigman describes how she spent a couple days ‘caring’ for the tree; tidying up around its roots, removing unattractive stones and pebbles, trimming “small extraneous branches” and generally preparing it for a photograph that she might never take. In a way, her preparation of the scene is reminiscent of the Japanese cha no yu tea ritual, in which the unseen preliminary activities are as important to the process as the final result. The careful preparation puts the person in the proper frame of mind to make the tea — or take the photograph.

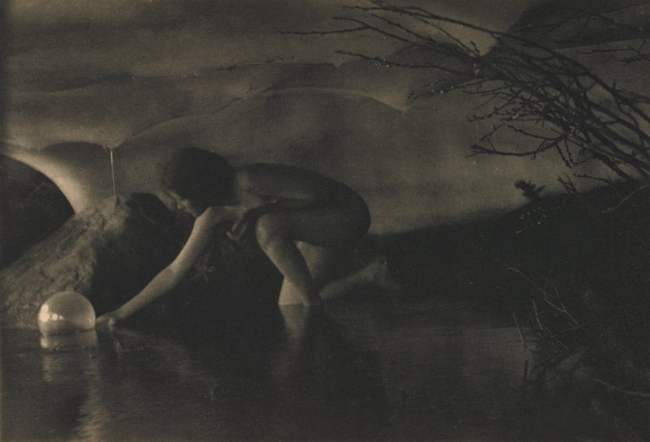

Brigman’s approach to photography seems to have been influenced by a strange blend of pagan mythology, European Romanticism, and her childhood exposure to the native beliefs of the Hawaiian people. Other artists had photographed nude subjects in natural settings long before Brigman. What made her work different is she saw her subjects as integral to the setting. To her, the people she photographed were just as much a part of the natural world as the trees and stones. She wasn’t photographing people IN nature; she was photographing people AS nature.

“In all of my years of work with the lens, I’ve dreamed of and loved to work with the human figure — to embody it in rocks and trees, to make it part of the elements, not apart from them.”

She often sought to do that by portraying people as mythical, magical creatures. She once described much of her work as “the partially realized fancies that flourished in the golden or thunderous days of two months in a wild part of the Sierras where gnomes and elves and spirits of the trees reveal themselves under certain mystical incantations.“

Not surprisingly, Brigman’s free spirit, her growing reputation as a photographer, and her willingness to nurture other artists attracted young photographers. Dorothea Lange, Edward Weston and Imogen Cunningham all made pilgrimages to Brigman’s studio, and all would later credit her as one of their inspirations. Some of these young photographers would accompany her in her long excursions into the Sierras and pose in her juniper friends.

In 1929, at the age of 60, Anne Brigman moved to Long Beach, California. Her work became more introspective, more abstract, and considerably less popular. She began to photograph the beaches of California and appeared to be especially intrigued by patterns created in the sand by wind and surf. That work received little critical attention. Her earlier style of dramatic pictorialism became increasingly seen as quaint and affected, and Brigman began to fade from view in the photographic world. She died in 1950; she was 81 years old.

Anne Brigman and her work were somewhat resurrected by the late twentieth-century eco-feminist movement. Her willingness to go to extreme lengths to explore her art, to defy the traditional roles of a woman of her era, and to fully integrate the nude female body into the landscape brought her a new appreciation by a new audience.

Brigman’s work IS terribly dramatic, but it must be remembered that she lived a dramatic life in an era when drama was still untainted by cynicism or irony. At a time when decent Christian women in the U.S. were expected to be modest and to achieve fulfillment in motherhood, Anne Brigman was trekking up into the mountains in trousers — a scandal in itself — carrying a heavy pack of camera equipment. There she shucked off societal expectations along with her pants, and entered into a pagan world inhabited by dryads and water nixies. And there she made art.

Anne Brigman’s photographs may, in fact, be the least dramatic thing about her.