Los Angeles. Tradition names it the City of Angels. Orson Welles called it “that bright, guilty place.” In modern pop culture it’s known as ‘La La Land.’ In an earlier era, L.A. was said to be where intellectuals went to ruin themselves. In its long history (it was founded by the Spanish in 1781), the city has been described as both utopia and dystopia. Both descriptions are correct.

It’s always been a city of migrants. First they came for the agriculture. Then, in the 1920s, for the film and later for the aerospace industry. They all came to Los Angeles with dreams, and some of those dreams actually came true. One of those migrants was a thirty year old man, the child of an itinerant military family and a Vietnam veteran himself, bringing with him a degree in philosophy, an MFA, and a camera. His name is totally unassuming, a name out of a bad Hollywood script: John Humble.

Like Alexey Titarenko and Brassaï, who found their muse in their respective cities, Humble has traversed the limits of Los Angeles. If L.A. lacks the romance of Brassaï’s Paris or the deeply stratified history of Titarenko’s St. Petersburg, it has its own strange and elastic personality. Covering more than 450 square miles and holding over three and a half million people speaking more than a hundred different languages, Los Angeles is rich and poor, beautiful and ugly, urban and suburban, totally real and absolutely illusionary. It’s its own place.

In 1979 Humble was one of eight L.A.-based photographers awarded a grant from the National Endowment for the Art to document the city in anticipation of its bicentennial. The project was called the Los Angeles Documentary Project; its stated purpose was “not to document Los Angeles stereotypes and clichés but to show the city that few had cared to photograph.” No Hollywood signs, no Griffith Observatory, no Union Station. Instead, they wanted the L.A. that tourists never saw, the L.A. where people lived and worked.

Eventually the grant money ran out–as grant money always does–and the project was completed. But Humble never stopped photographing the city. He continued to roam the entire breadth of Los Angeles, seeking and finding beauty in its nondescript neighborhoods.

But he didn’t roam at random. He roamed with a purpose. Humble was engaged in what he came to call ‘sociological archaeology.’ In effect, he began to more thoroughly complete the original intent of the Los Angeles Documentary Project; he began to slowly, carefully, and very deliberately scrape away the sedimentary layers of media-driven images of Los Angeles to find out what lay hidden beneath. In doing so, he uncovere–and photographed–some unique patterns of social relationships, social interaction, and culture.

Like so much associated with the city, the Los Angeles River challenges common sense and notions of normality. For most of its 51 mile length, the L.A. River flows through a concrete channel, forcing one to consider the question of what actually constitutes a river. Until the construction of the Los Angeles aqueduct in 1913, the river provided up to 80% of the city’s fresh water. Now it’s primarily a conduit for channeling tertiary sewage runoff and polluted rainwater to the sea.

The L.A. River bisects the city. Homeless people find shelter under the bridges that cross it and, during the dry season, in the storm drains. Poor and working class families reside along the concrete banks in modest suburban-style homes. Industrial ‘parks’ and commercial structures squat beside the channel. There is a movement by environmental groups to remove the concrete and restore some element of natural vegetation to the banks, but for the most part the river is disregarded and overlooked.

For a photographer like Humble, though, the river is like a magnet that attracts irony. Not only does the river’s course through the city provide countless examples of urban incongruity, its very existence is ironic. The city would not have existed if not for the river, and yet the city has removed almost every trace of what makes it a river. Still, if properly approached, the Los Angeles River offers an otherwordly, dystopian beauty. Humble finds that beauty and treats it with respect.

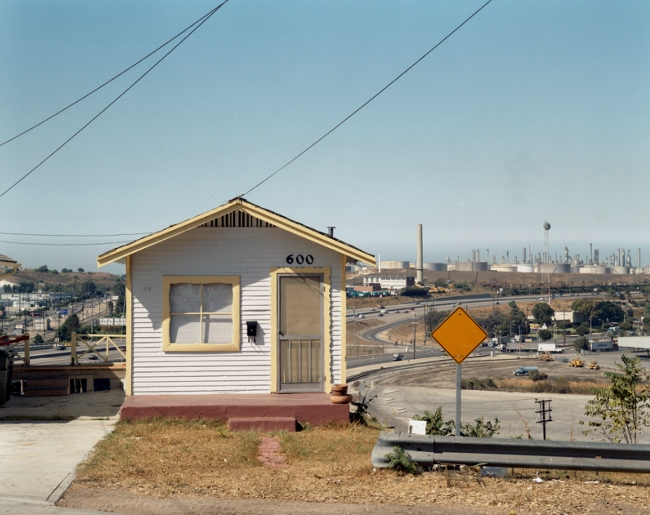

Among its many nicknames, Los Angeles could also rightly be called the City of Internal Combustion–in every sense of the phrase. The car is king and the city is crisscrossed by a staggering maze of highways and bypasses, expressways and overpasses, transit lanes and cloverleafs. More than 500 miles of freeway and nearly 400 miles of conventional highway overlay Los Angeles. Humble hasn’t photographed it all, but no exploration of the city could ignore the centrality of the highway system.

Highways are ubiquitous in Humble’s work. Not only are they the central subject matter of many photographs, they’re often deliberately included in the background of other images. In effect, the L.A. highway system serves the purpose that the L.A. River might have served in an earlier time: it is the artery that gives life to the city, the conduit that carries life through the city. In keeping with the ironic nature of L.A., the highways both keep the city alive and, by polluting its air, ruin its health.

Armed with a 4×5 view camera and an old van, Humble studied and celebrated L.A.’s highway system in much the same way Ansel Adams studied and celebrated Yosemite and the Tetons. In doing so, Humble gives a sort of transcendent majesty to the L.A. highways. Through Humble’s lens, the highways become more than merely a semi-efficient mechanism for transportation; they become a cultural artifact. The highway system is as representative of modern Los Angeles as the Great Wall is of ancient dynastic China, or the system of aqueducts is of the Roman Empire.

It’s easy to love Paris; it’s a city of great beauty that inspires passion and romance. It’s easy to love St. Petersburg, with its heart-breaking history and its cultural splendor. To love Los Angeles requires more effort, more patience, more tolerance. Humble doesn’t just love the glitter of L.A., nor is he smitten only by the city’s darker angels; he does something more difficult still. Humble somehow manages to love the vast expanse of mediocrity that supports both the glamour and the dark side. He loves it and in turn makes it lovely.

That’s a very special sort of love.