William Joseph Eggleston turned 70 on July 27, 2009—less than a week ago. He was born in Memphis, Tennessee in 1939. Shortly thereafter his father left to serve as a gunnery officer on a destroyer attached to the Pacific fleet in World War II. Baby William and his mother went to live with her parents, who owned the Mayfair plantation—five thousand acres of good cotton land on the Tallahatchie River, just outside of Sumner, Mississippi.

Eggleston’s childhood was divided between the plantation manor and the family’s winter home in Sarasota, Florida. “I guess you could say my childhood was idyllic,” he’s said. “The sharecropping system was still in force, and we were the privileged class.” His family had great respect for the arts. “The first two things given to me as a child by my mother…were books on Rouault and de Chirico.” His maternal grandfather, a dedicated amateur photographer who had a darkroom built in the house, gave Eggleston his first camera when he was ten years old. Photography, though, failed to hold his interest and he soon set the camera aside.

In his teen-aged years, Eggleston’s interests appear to have been divided between high-end audio equipment, painting, and his baby-blue Cadillac. He enrolled at Vanderbilt University in 1957, where a friend talked him into making a spontaneous purchase of a 35mm camera. Eggleston began to tinker again with photography, although apparently with limited enthusiasm.

That lack of enthusiasm, it seems, wasn’t due to the limitations of the camera or the process of printing; it was more a result of the state of photographic art in the United States. Art photography at the time was essentially the province of large format photographers like Edward Weston and Ansel Adams—photographers who worked slowly and meticulously both in the field and in the darkroom. Robert Frank, of course, had recently finished his travels around America and was on the verge of subverting everything thought holy to American art photography—but Eggleston wasn’t aware of that.

While at Vanderbilt, Eggleston did, however, stumble across a book by French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson: The Decisive Moment. And that changed everything. Eggleston was very taken by the sort of planned spontaneity of Cartier-Bresson’s work, by the sense that the image relied as much on the photographer’s intuition and his unthinking notion of composition as it did on the subject matter in front of the camera. It wasn’t just about the moment; it was about knowing enough to be in the right place—and more importantly, in the right frame of mind—to take advantage of the moment.

“I couldn’t imagine doing anything more than making a perfect fake Cartier-Bresson.”

Eggleston, with practice, discovered he could do just that. But copying the master wasn’t entirely fulfilling, for at least two reasons. First, there was something distinctly European about Cartier-Bresson’s work which Eggleston knew he’d never be able to replicate. He’d traveled to Paris, but hadn’t felt the desire to photography anything. Second, he had an abiding interest in Abstract painting and graphic design. Why was that important? Because it also meant he was interested in color.

It’s difficult now to fully comprehend the attitude of the fine arts photography community toward color. Color had been used in cinema since the late 1930s. Color television was introduced in the 1950s. Color film for still cameras was widely available, But to art photographers, color was seen as contemptible. It was considered suitable for some things—advertising, of course, and possibly some news photography. But color film certainly wasn’t appropriate for fine art.

One rarely mentioned factor that surely played some role in the aversion of art photographers to color film was that it was notoriously difficult to develop at home. That meant photographers had to rely on others to process their film and print their work. They had to give up a great deal of control over the final print—and this was especially discomfiting at a time when control over the print was seen as the ultimate photographic act.

Beyond that, color was seen as a distraction from the purity of form and line. Color introduced a complicating element in composition. Color was commercial. Robert Frank, whose photography for The Americans changed modern photography, said “Black and white are the colors of photography.” Walker Evans put it this way: “There are four simple words on the matter, which must be whispered: Color photography is vulgar.”

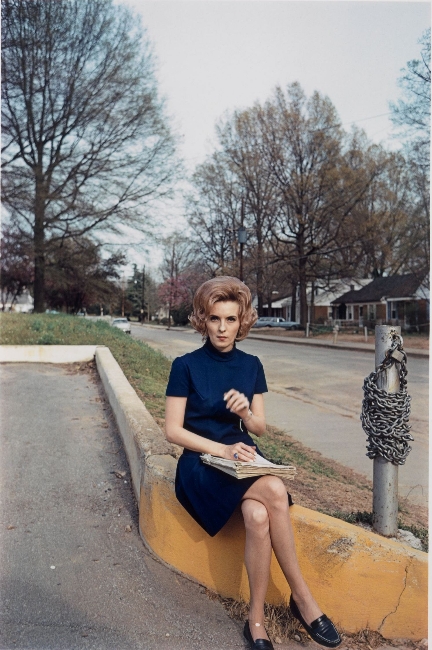

Eggleston, remember, was raised as a Southern gentleman, in a tradition of Southern gentility. Vulgarity might be socially unacceptable, but artists often experience a gravimetric attraction to the forbidden. Eggleston wasn’t afraid of being vulgar. He set a mission for himself. He decided to seek out ‘foreign’ landscapes in his own community, he would look at those landscapes with an alien eye, and he would photograph them in color. His earliest ‘foreign’ landscape was the new commercial phenomenon of the shopping center. What could be more vulgar?

“I had this new exposure system in mind, of overexposing the film so all the colors would be there. And by God, it all worked…. The first frame, I remember, was a guy pushing grocery carts.”

Eggleston wasn’t the first to work in color, of course. Other art photographers in other places—mostly in New York City—were also experimenting with color photography. Unlike Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand, though, Eggleston’s approach wasn’t grounded in daily life on the streets. Instead, his work was based on the novel notion that everything was worth photographing when seen through alien eyes. Even the most commonplace and mundane things, when seen as if for the first time, could be as fascinating as any deliberately created beautiful object. This concept—that nothing is more important or less important than anything else, that people and objects can be treated visually with the same dispassionate fascination—has become known as ‘the democratic camera.’

Eggleston’s use of color became more extreme when he discovered the dye transfer process—an expensive printing technique that allowed him to control the intensity of individual colors without disrupting or influencing the complementary colors. The resulting prints were extremely vivid.

Although his work began to attract attention and was exhibited occasionally in galleries it wasn’t until 1976, when Eggleston was in his mid-30s, that he really began to influence the photographic art world. That year the Museum of Modern Art in New York City displayed forty-eight of his photographs This wasn’t the first time MoMA had exhibited color photographs (although the Eggleston show is sometimes described that way), but it was the first time color photography elicited such a powerful reaction. The exhibit received wildly dissimilar responses from critics and photography-lovers. The curator of the exhibit, John Szarkowski, called the photographs “perfect…a paradigm of a private view, a view one would have thought ineffable, described with clarity, fullness, and elegance.” The New York Times art critic, on the other hand, called them “perfectly banal…perfectly boring.” Another critic called it “the most hated show of the year.” Regardless of whether their response was positive or negative, nobody could ignore the photographs. Even those who thought the subject matter was forgettable, couldn’t forget the impact of the photographs.

There is something almost hallucinatory about Eggleston’s photographs, both in their use of vibrant color and in content. Although he has something of a reputation for hard living, I’ve never seen anything to suggest Eggleston ever used LSD. It may be entirely coincidental that LSD was still legal in 1965 when he began his experimentation with color photography. But his fascination with the mundane, his absorption in detail, his willful disregard of the borders of the frame, his attraction to shooting from unconventional and disorienting angles—these aspects of his work resemble the visual experience of being high on a low dose of acid.

The content of Eggleston’s photographs almost never matches the intensity of the act of seeing. Even when the colors are muted, it’s the conscious act of observing that drives the work. Consider, for example, the photo of the empty tables in some anonymous small-town diner. It’s a rather nondescript scene, one the eye would easily pass over in life. When you take the time to see it, the photo is very revealing. The mis-matched chairs, some of which have been matter-of-factly repaired by the very practical application of duct tape; the identical linoleum-topped aluminum tables; the wall decorations, which are simply plastic flowers attached to what appears to be egg-cartons; the Texas Pete’s Hot Sauce bottle on the table filled with toothpicks. These things tell the viewer a lot about the people who own and run the diner, as well as about the people who gather to eat there. Even though there are no people in the photograph, we are nonetheless very much aware of their existence.

Eggleston has been a force in art photography for more than three decades now. His work still remains controversial. People continue to look at his work and say “My five year old could have taken that picture.” And there’s some truth in that. Some truth, but not much. There is a sort of five-year-old’s artlessness to his work, but it’s a deliberate artlessness. Eggleston understands what he’s doing, and he’s very much aware why others, including a great many photographers, don’t understand what he’s doing.

People, Eggleston says, “want something obvious…. I am at war with the obvious.” What’s not obvious is that Eggleston, at heart, is a romantic. We’re used to seeing romanticism in more overt ways—dramatic skies, towering mountains, spectacular sunsets, soft lighting, lonely beaches. Eggleston’s look at an old child’s tricycle is a romantic look. It’s an innocent look at an innocent plaything. Looking at it, with its rusty handlebars, we can’t help but think how much delight that trike brought some child—we can’t help but compare the joyful trike with the pragmatic family sedan parked in the carport in the distance. Eggleston’s look at an old advertising sign atop a corrugated metal roof is a romantic look. It doesn’t matter that the sign is faded, or that roof is decrepit; we look at the photo and we automatically think of the simple pleasure of peaches—ripe, juicy peaches. Or, as the sign says, Peaches! The exclamation point is perfect.

Eggleston’s democratic camera contradicts what we’ve learned to expect from art; it contradicts what we’ve learned to expect from romantic vision. His revelation of the exhilarating ordinariness of daily existence sometimes confounds us. Eudora Welty, the great Southern writer, wrote this in the Forward of Eggleston’s book, The Democratic Forest: “When you see what the mundane world so openly and multitudinously affirms, there is everything left to say.” That’s why Eggleston believes everything is worth photographing.

And that’s why your five year old can’t really take photographs like William Eggleston.