How does one measure a successful life? Is the proper metric a rewarding career? A loving relationship? Contentment with the choices one has made? More joy than regrets? What if you lived a long, fulfilling life doing important and interesting work, a life replete with friendship and love, a life lived on your own terms—what if you had all that, but the one thing that you wanted to succeed at the most, the project closest to your heart during your most productive years, what if that turned out to be a failure?

Homer Page worked as a photojournalist for a good part of his life, covering stories around the world. In the early 1950s he was associated with the Magnum Agency. He worked stories in Africa, India, Laos, Indonesia; he worked in the Caribbean and in Latin America. In 1957 he produced possibly the first major photojournalism feature on a nun working with the poor of Calcutta, a woman who later became known as Mother Teresa. He did stories on juvenile delinquency and cancer research and the civil rights movement in the American South; he did stories on the Peace Corps and the beginnings of the environmental movement.

Gradually over time he became more journalist than photographer. As he became more intrigued and impassioned by the back-to-nature movement in the mid-to-late 1960s, Page and his wife moved to a five acre parcel of woodland in Connecticut, part of a 750 acre nature cooperative. He made furniture and split his own rails for fencing, he hand-crafted iron tools—everything from shovels to scissors. He died in 1985 at the age of 87, in a house he’d designed and built himself.

Like anybody who lived a long and active life, Homer Page surely had his share of regrets as well as successes. It would be presumptuous of me to try to classify those regrets. But surely near the top of the list would be the failure of his Guggenheim Fellowship.

Page was born in Oakland, California in 1918. His interest in photography grew out of a promotional stunt by the Kodak company. In 1930 Kodak gave free Brownie cameras to school children across the nation. Page, 12 years old at the time, was one of the lucky recipients. He learned to use the camera and by the time he was in high school (which he attended in Los Angeles) he’d bought a 35mm camera and had set up his own darkroom. During his high school years Page began shooting what he called “candid” photos of people in and around L.A.’s Pershing Square, which was a fairly rough neighborhood at the time.

He attended the University of California, initially studying business administration before switching to social psychology, which he later abandoned for a major in Art. He met and fell in love with and married a fellow student, Christina Gardner, also an enthusiastic photographer. After graduation in 1940, Page took a job at glass company while Christina completed her studies. Their lives were interrupted by World War II. Page was rejected for military service because of a punctured eardrum, so he found employment in the shipyards—his way of contributing to the war effort. With the money he earned from his first real job, Page bought a twin-lens reflex Rollieflex camera. In his free time, he use the sturdy TLR to shoot “candid” photographs of the men and women who worked in and around the shipyards. Christina, in the meantime, accepted a position as an assistant for Dorothea Lange, already recognized as one of the nation’s best photographers.

Lange encouraged both Page and his wife. At her suggestion he sent some of his photos to the Museum of Modern Art. Although MoMA didn’t purchase any of the photographs, the acting director was very encouraging and asked that he periodically send in more of his work. Around the same time, Page started a personal project photographing delinquent and troubled juveniles. Many of the resulting images were published as an article (The Question of the Kids) in a camera magazine; others were shown at MoMA as part of an exhibit on rising photographers.

His success with the delinquent children project had two significant results. First, it sealed Page’s desire to become a professional photographer documenting social issues. Second, it sparked an internal debate in his mind. What was he trying to do—create art or document social situations? How did he want the images to be received—as striking and memorable photographs or as vivid illustrations of life circumstances? What was his target audience—magazines or galleries? Was he primarily an objective recorder of reality or was he expressing his own singular perspective through art?

In 1944 Page quit his job at the shipyard and began to devote all his energy to photography. He accepted freelance work, he spent a year as the official photographer for a University of California organization, he began to teach photography part time at the California School of Fine Arts. His work was garnering more attention, especially in the art world. He even found support from the new curator of photography at MoMA—Edward Steichen. In 1948 Page moved to New York City to work part-time for Steichen; his wife followed a few months later.

Earlier, Dorothea Lange had encouraged Page apply for a Guggenheim Fellowship (she’d been a recipient herself in 1941). With Steichen’s support, he finally sent in an application in 1948. In the application letter, Page stated he wanted to photograph the “relationship between urban people and the cultural forces which surround them.” He also wanted to “organize these pictures into a dramatic form that has a flow of development.” In other words, a book.

This may sound similar to a Guggenheim application by another photographer, Robert Frank, who went on to create the seminal photographic series in modern American photography. It’s important to remember, though, that Homer Page made his application seven years before Frank.

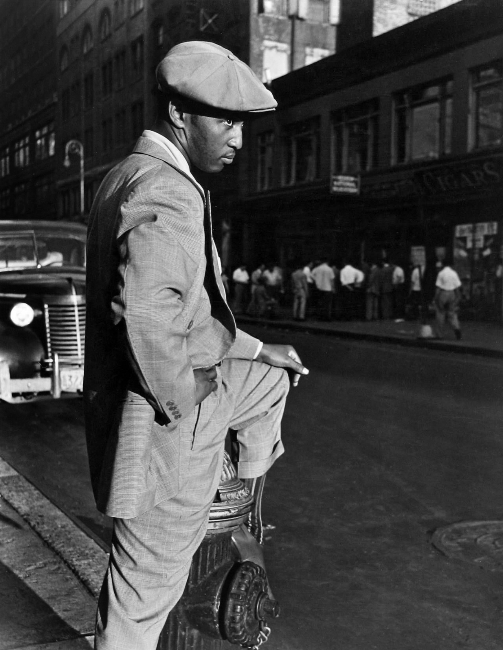

Page’s application was accepted and in April of 1949 he began his year as a Guggenheim Fellow. Armed with a new 35mm Leica camera bought with his grant money and his trusty old twin-lens reflex Rolleiflex he began to photograph New York City using the style he’d developed around the shipyards of Los Angeles and Oakland—a style that would eventually develop into what is now called ‘street’ photography.

Almost immediately Page realized his original plan was wildly over-ambitious and vague. In a letter, he wrote: Some days everything I see seems to be important; other days, nothing. He also found it nearly impossible to shoot the photographs and take reliable notes regarding what was being photographed, which was a serious concern if he wanted to document the “cultural forces which surround” urban people.

Part of the problem was that post-war culture in the U.S. (and, indeed, throughout the entire industrialized world) was changing rapidly. The U.S. had , in the preceding two decades, survived the Great Depression and a war that spanned the globe, and were now facing what the government was calling the “Red Menace” of communism and the possibility of atomic warfare. Art was changing, music was changing, modes of transportation were changing, television was becoming ubiquitous. The existentialist movement was taking hold of creative minds, while at the same time there was a drive toward conformity and conventionality based on a powerful desire for normalcy after the war.

In a lecture Page gave shortly after accepting the Guggenheim Fellowship, he said: “We are not sure of war or peace, prosperity or recession; not sure what balance to strike between our freedom and our security, either as a nation or as individuals. The fundamental issues are clouded and almost certainly in transition. This makes any attempt to record conditions extremely difficult.” Later, he said, “If confusion of values is an important part of our life today, we must analyze and record this confusion.”

And that’s what Page ended up doing. The photographs from his Guggenheim year are precariously poised between the balance and order of an earlier era and the embrace of diversity and chaos of the coming era. His work isn’t entirely documentary, nor is it unabashedly street photography. It’s transitional photography made during a transitional period; uncertain imagery of uncertain times. But one consistent aspect of those photographs is Page’s attention to detail and to the individuality of his subjects. These are compassionate photographs.

At some point along the way, Page essentially abandoned his Rolleiflex and relied almost exclusively on the light and agile Leica. He recognized that his work wasn’t what it had been at the beginning of the fellowship year, and he wasn’t entirely sure where it was going to end up. He wrote to Dorothea Lange, You will notice that my seeing is changing, and though I have no alternative but to follow my eye, I wonder what you think about it…. The newer images more suit my ambivalent and confused state of mind.

In early 1950, as his Guggenheim year approached its end, Page requested a second year of support. That request was denied. The stress of that year—which included a move from California to New York City, inhabiting a tiny tenement apartment in a questionable neighborhood, the high cost of living in New York, and Page’s intense focus on his work—shattered the Pages marriage. Christina moved back to California with their daughter. Although Page shopped the photographs around to various publishers in the hope of getting a book contract, nobody showed any real interest in his work.

Page eventually gave up. He put his Guggenheim prints and negatives into storage boxes, put them away, and ignored them. He went on to other photographic pursuits, then to journalism, then to living a simple life on a small plot of land. The world of photography moved on without him and he was essentially forgotten. A search of the Magnum Photos website reveals only two photos relating to Homer Page—and they’re portraits of Page taken by another Magnum photographer.

Homer Page was a pivotal figure in a pivotal moment in the history of photography, but his work failed to take root. Was it the fault of Page or the times he lived in? Were the photographs inherently flawed, or had the public’s visual awareness not yet evolved enough to appreciate them?

How does one measure a successful life? Perhaps one measure is that sixty-odd years after Homer Page’s year as a Guggenheim Fellow and twenty-some years after his death, those photographs were removed from their storage boxes by his third wife and again presented to publishers. Perhaps one measure of success is that, at long last, the Guggenheim photographs were made into a book (all of the photographs above were shot during Page’s Guggenheim year). Maybe one measure of a successful life is that his photos have finally found the right audience.

And maybe the ultimate measure of a photographer’s life is the courage to follow his or her eye wherever it leads, even if it appears to lead to obscurity.