“What’s always interested me in photography is the way you can play with reality. Photography is based on reality, it looks like reality, but it’s not reality.”

The interviews I’ve read with Richard Kalvar suggest he’s not a particularly articulate man. He struggles, it seems, to put his thoughts into words. That’s a shame because it seems clear his thoughts about photography are pretty profound.

In the comment above, for example, Kalvar is speaking on several different levels. On one level, he’s simply stating the obvious: a photograph of a thing is not the thing itself. On a second level, though, he’s talking about how photography strips away other sensory and temporal information – smell, sound, touch, motion – from what’s being photographed. Those things aren’t in the photograph, and yet they can be suggested through the photograph. On a third level Kalvar is referring to the fact that a photograph is a moment out of context, and as such it can’t be trusted in the way reality can be trusted. Things happen before the photograph was taken, and they continue to happen afterwards. And on yet another level, he’s acknowledging the Rashoman quality of all photography – that a photo conveys only one view of a thing that happened, but any number of views could be completely different and yet just as honest.

This is what has drawn Kalvar to photography, and particularly black-and-white photography, for almost half a century. The mystery of the moment when that moment is removed from the ongoing world. That sounds very abstract, and it is; but Kalvar is very practical about the abstract. “It’s what I like to do,” he says.

Kalvar was born in Brooklyn in 1944 to a family he describes as “relatively poor.” My impression is he comes from the working class, where people have jobs instead of careers. “You could always get a job,” he told an interviewer, “drive a taxi, work in a restaurant.” He apparently spent most of his high school years “screwing around,” as he puts it. Kalvar discovered he had something of a creative spark during those years, but didn’t have any outlet for it. Nor does he seem to have given much thought to the matter, aside from simply realizing he was more inventive than his friends.

Somehow Kalvar managed to get into Cornell University, where he studied literature. He dropped out of college in the mid-1960s and returned to New York City and started looking for a job. He found one with Jérôme Ducrot, a fashion photographer. Kalvar didn’t have any real interest in photography at the time, and no interest at all in fashion photography. He learned about photography simply because it helped with his job.

According to Kalvar, Ducrot “had a broad knowledge of photography and was a smart guy and who introduced me to things outside of fashion photography. He showed me books.” He worked for Ducrot for about a year, quitting after what Kalvar describes as “a big fight.” Whatever the argument was about, it didn’t ruin their relationship; Ducrot gave Kalvar one of his cameras – a Pentax – as a parting gift.

Kalvar had managed to save a small amount of money during his year with Ducrot. He decided to spend it on a trip to Europe. He very nearly didn’t take his camera with him. “I had this big knapsack, and I tried to squeeze everything in, but I couldn’t get the camera in, and I thought ‘Well, should I really take it?’ But then I pulled something else out, and stuffed the camera in, thank God.”

That last minute decision led to Kalvar’s eventual career as a photographer. He banged around Europe for some time. The goal, he says, “wasn’t to take pictures but just to have an adventure.” He did take pictures, though, and sent the film back home to his father. He never saw the result of his photographs until he returned to the States ten months later. “But I knew,” he said.

“I knew at the end of the trip that this was for me – that I’d found something that corresponded to the screwing around I used to do with my friends – I could express myself, express a way of seeing, a way of being, through photography.”

When he returned to New York, Kalvar found a job as a receptionist at Modernage, a photo processing lab (which, by the way, still exists at 555 8th Avenue in the Garment District). “They let me stay in the evening and print for myself,” Kalvar said. “I printed up all the stuff I shot in Europe. I had a number of pictures I thought I liked. I started showing them around, and other people started to like them too. I had this feeling that I was going in this direction, that I was looking for something, which is similar to what I’m still doing today.”

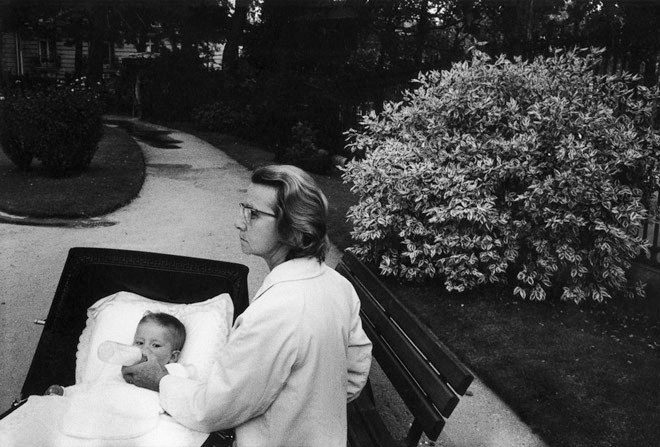

Most often critics describe that ‘direction’ as street photography. It’s not a description Kalvar likes. “It’s not necessarily done on the street,” he says. But that’s not the extent of his problems with the description of his work as street photography. He feels his work isn’t so easily definable. He thinks of his work as “unposed pictures of people,” but acknowledges they could also include photos of animals or inanimate objects “when they happen to be possessed by human souls.” But even that’s not quite accurate, because the photos Kalvar is after are about moments “with nothing particularly important going on.” And then he narrows it down even further, to include an element of play.

So Kalvar might, presumably, describe his goal as creating playful, unposed photographs of people or anthropomorphic animals or objects not engaged in doing anything of importance.

That’s a commendable goal, to be sure – but it doesn’t pay the rent. In order to shoot the sorts of photographs he wanted to shoot, Kalvar sought out any sort of photographic gig that would pay money. “Women’s magazines, things about knitting, anything to make a living.” He continued to shoot the photographs he wanted to shoot in his own time.

He still follows that path, in fact, though he’s come a long way from photographing knitting. The combination of his personal photography and his professional photography eventually led him to be recruited by Magnum, the international photographic cooperative. He now has a home in Paris, where he’s lived since around 1970. “I can do company portraits. I go there and get a nice picture of the guy that they can put in their annual report,” he says. That’s a rather dismissive way to look at his professional work, which often includes photojournalism assignments for major magazines. But Kalvar makes it very clear that there’s some degree of separation between what he does to earn money and what he does for self-expression.

For one thing, his professional work is almost entirely in color; his personal work is exclusively black-and-white. Why?

“In order for the mystery to work, you need abstraction from reality. Black and white is an additional abstraction, in addition to selective framing, to the freezing of the moment that in reality is a part of an infinite number of other moments…you have one moment and it never moves again; you can keep looking at the picture forever. The black and white is one more step away from reality. Color, for me, is realer, but less interesting.”

“I’m an amateur photographer and a professional photographer,” Kalvar says. “I’m a much more interesting amateur photographer than I am a professional photographer.” His professional work is done on assignment, obviously. So how does he approach is personal work?

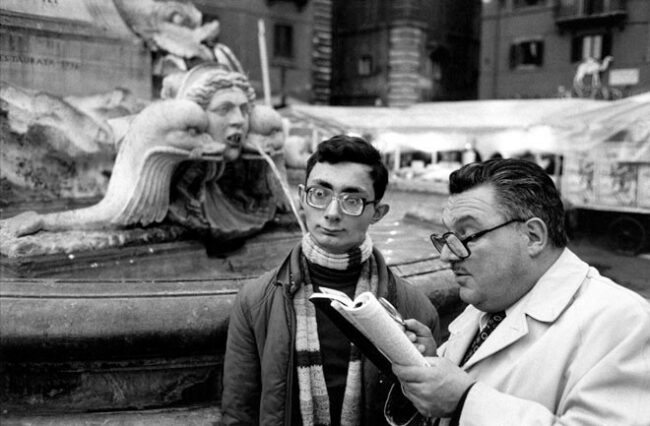

He uses a Leica and he walks around a lot. “That’s necessary. I try to go to places where interesting things might happen. And I’m always looking. At relations between people. I’m attracted to people doing things with each other.” He looks for people engaged in conversation, then he lurks nearby, waiting to see if something interesting happens. To get the sort of photograph he wants requires a combination of being in the right place and being ready.

“In French, there’s a word, disponible,” he says, “meaning you’re letting yourself go, you’re available for things to happen. It’s a mental and emotional opening. In other words, you’re ready.” This corresponds pretty closely to the state Cartier-Bresson describes when he’s in search of his ‘decisive moment.’ It’s a sort of melding of heightened awareness, sensitivity to the moment, and a passive abandonment of concentration until it’s needed.

“I take a lot of lousy pictures,” Kalvar says, in his attempts to get the rare photograph that meets his personal criteria. He’s not always aware of when he’s successful. “There’s a certain irrational element that afterwards I can describe and try to analyze. I look at [the contact sheets] and suddenly I see, amid all the crap, something that sticks out and works – and works in a way that has a kind of hysterical tension in it.” There are also times when he’s missed out on photographs simply because he’s uncomfortable with the social circumstances. “I’m kind of shy and sneaky and aggressive at the same time,” he says. “Sometimes I have the nerve, sometimes I don’t.”

Kalver’s notion of a good personal photograph has to meet a pretty strict criteria. He’s been shooting photos for nearly half a century now, and in his most recent show there were fewer than 90 photographs he felt worked well enough to exhibit.

I’ve largely ignored Kalvar’s professional accomplishments in this essay. I didn’t mention, for example, that he started the Viva photo agency in France in 1972. I noted that he was a member of Magnum, but I didn’t reveal that he began as an associate member, then became a full member, or that he’s served as both vice president and president of the agency. I didn’t mention any of his shows, or his book Earthlings (released in 2007).

I’ve ignored those aspects of his career primarily because I think they’re less important to Kalvar than being out in the world walking around, alert to events around him, open to the moment, disponsible. I’ve ignored those things because reality is less interesting to Kalvar than those moments that bend and distort reality, that curve reality into a shape that suggest many possible realities.

“A photograph is what it appears to be. Already far from ‘reality’ because of its silence, lack of movement, two-dimensionality and isolation from everything outside the rectangle, it can create another reality, an emotion that did not exist in the ‘true’ situation. It’s the tension between these realities that lends it strength.”

We all share a reality with Richard Kalvar. But we’re not all privileged to see it in the same way he does.