It’s Fashion Week in New York City. Twice a year in the major fashion capitals of the world (New York, Paris, London and Milan) designers preview the release of their new designs. Trends are set (or fail), reputations are made (or lost), and millions of dollars are spent. In the autumn, designs for the coming spring and summer are revealed; in the spring, autumn and winter designs are released. In effect, fashion week is about predicting the future – it’s about trying to foresee what people will want to be wearing six months from now.

Obviously, Fashion Week is also an important time for fashion photographers. It seems fitting, then, to look at the unpredictable career of a fashion photographer whose future couldn’t possibly have been foreseen – a photographer who made her bones in the 1950s, who became one of the leading lights in fashion photography, who abandoned the business and disappeared from view for half a century, and who has in recent years been resurrected as a fashion icon.

I’m talking, of course, about Lillian Bassman.

Like so many of the photographers we’ve examined in these salons, Bassman didn’t originally intend to become a photographer – it just sort of happened. When she found her way to photography, it wasn’t so much a career move as it was an organic evolution of expression.

Lillian Violet Bassman was born in Brooklyn on June 15, 1917, the child of Russian émigrés. Her parents were Jewish intellectuals and Bassman was raised in a manner that could best be described as bohemian. She and her sister “slept on couches on the floor covered with batik covers,” she told an interviewer. “We had only one thing that we had to do. Iron our own uniforms and wash our hair on Saturday. Otherwise we could be as free as birds.”

Her mother worked as a waitress in a vegetarian boarding house on Coney Island. When Bassman was six years old, she was introduced to Paul Himmel, the nine-year-old son of her mother’s employer. They became fast friends and that friendship developed into something more. When she was 15 years old Bassman convinced her parents to let her move in with him. They married ten years later – and remained married for the rest of their lives. Himmel died in 2009; they’d been married for 73 years.

It was Himmel who was initially interested in photography (he would eventually become good enough for his work to be included in Edward Steichen’s famous Family of Man exhibit at New York’s Museum of Modern Art). Bassman wanted to be a dancer, but an injury to her heel crushed that hope. Instead, she attended a vocational high school and studied textile design. She found part-time work as a model for artists employed by the Works Project Administration – the Depression-era government program designed to provide jobs carrying out public works projects. Modeling, she said, was “the easiest way to get my 50 cents an hour, which was a lot of money at that time.” That eventually led her to a job as an assistant painter creating murals for the WPA.

During the early lean years of their relationship Bassman and Himmel relied on free admission to local museums for entertainment. They would spend hours wandering the halls, studying the paintings of old masters. That time served Bassman well, though its importance wouldn’t reveal itself for years.

Bassman continued her education by taking night courses in fashion illustration. She got an interview with Alexey Brodovitch, the Art Director at Harper’s Bazaar and the creator of the exclusive Design Laboratory at New York’s New School for Social Research. Brodovitch, a Russian émigré like Bassman’s parents, was impressed enough by her work that he waived her tuition and accepted Bassman as a student in the Design Lab.

It was Brodovitch’s practice at Harper’s to have a few talented young women in the office to act as his unpaid assistants. He offered one of those positions to Bassman, who accepted – but she soon balked at the lack of pay. When she was offered a paid position as an assistant art director at Elizabeth Arden, a cosmetics manufacturer, Brodovitch made Bassman his first paid female assistant. Four years later, in 1946, Harper’s launched a magazine called Junior Bazaar, targeting teen-aged girls. Lillian Bassman was named its art director. And that changed everything.

Before her promotion, Bassman had been visiting the magazine’s darkroom on her lunch hour to see how photographer George Hoyningen-Huene used tissue and gauze to manipulate the printed photograph. “I was interested in developing a method of printing on my own,” she told B&W magazine in 1994. “I wanted everything soft edges and cropped.” At that point in her career she was more interested in the darkroom than in photography, more interested in the final printed image than in shooting the photograph. Bassman gave Junior Bazaar a look that matched her aesthetic.

As the magazine’s art director, Bassman often hired photographer Richard Avedon, who’d also studied at Brodovitch’s Design Laboratory. In 1947 Avedon left for Paris to shoot fashion collections. Knowing her interest in printing, he gave Bassman the keys to his studio so she could use his darkroom while he was away. In order to get the type of negatives she wanted to print, she taught herself photography.

The following year, 1948, Junior Bazaar folded. Brodovitch asked her what she’d like to do next. She told him “I think I’ll be a photographer.” She and her husband opened their own studio.

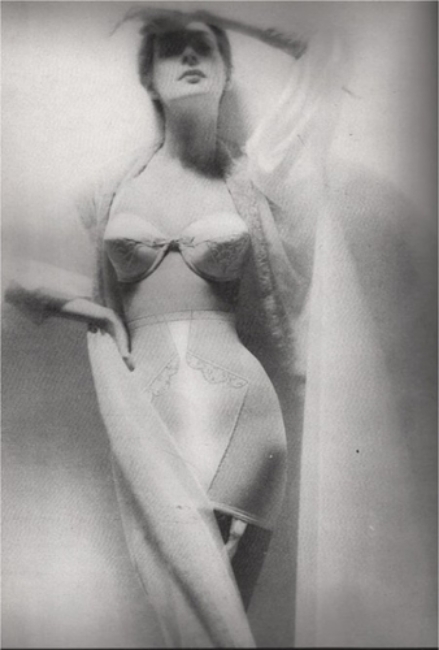

“I did everything that could be photographed,” Bassman said, “children, food, liquor, cigarettes, lingerie, beauty products.” But it was lingerie that made her name as a fashion photographer. To that point, lingerie advertising had consisted primarily of images of stout, middle-aged women with their heads cropped off posing uncomfortably in massively engineered girdles. Bassman used the same models other photographers used in fashion shoots. Because advertising norms insisted the faces of lingerie models be hidden or obscured, Bassman initially developed a technique using shadow to shade their faces (she would eventually abandon that practice, allowing the faces of her models to be seen). She refused to allow male assistants in the studio during lingerie shoots; she spoke to the models about their boyfriends and husbands, about their lives and their plans, and generally created an ambience of comfort and calm – all of which was apparent in the final prints. “[A]nd then I became the lingerie queen of New York and America.”

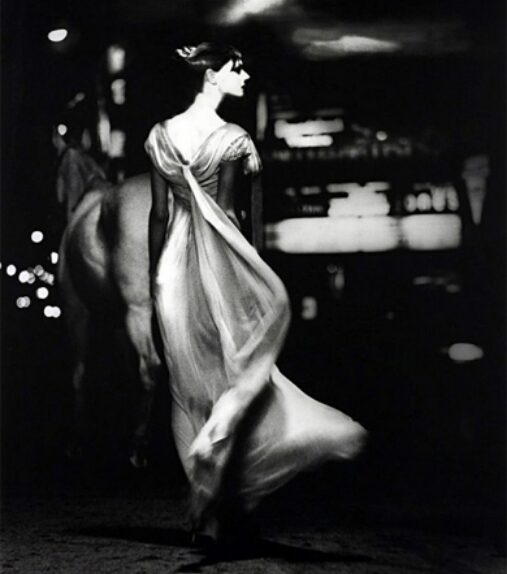

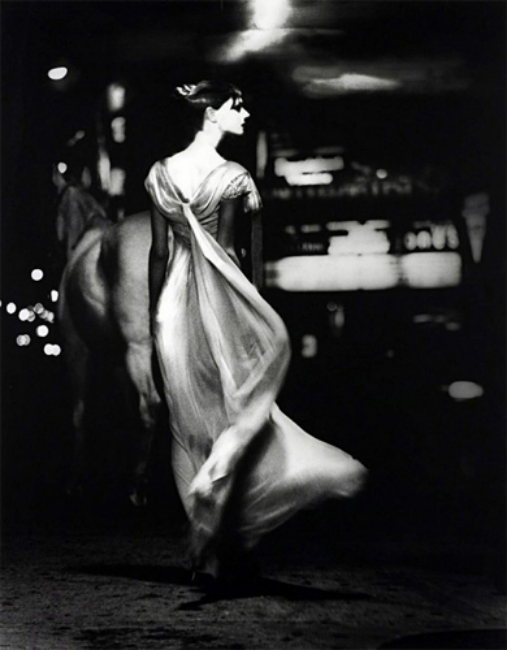

Lingerie work led to fashion work, and Bassman developed a reputation among art directors for creating elegant, serene, romantic images. The women in her photographs always appeared to be doing something; they weren’t simply standing around showing off their clothes. She preferred to shoot her models outside, using natural light – and though the shots were clearly posed, they had an organic, active feel to them while still emphasizing the classic ideal of feminine grace and refinement.

That style, according to Bassman, grew out of the time she and her husband spent in museums as young lovers. “Elegance goes back to the earliest paintings,” she said. “Long necks. The thrust of the head in a certain position. The way the fingers work, fabrics work.” Bassman’s style was also influenced by her early love of dance, and she encouraged her models to move with a fluid sort of feminine poise that, as she said, “usually passes unnoticed in everyday life.” Bassman used a light hand when directing her models, but she was very clearly directing them and expected them to follow her lead.

That changed in the mid-1960s. Bassman didn’t like the shift in the fashion industry as it adopted and commercialized the English Mod culture. Worse, she didn’t like the new breed of models – the precursors of the modern supermodel. They were much more resistant to direction from the photographer. “I got sick of them,” she said. “They were becoming superstars. They weren’t my kind of models. They were dictating rather than taking direction.”

And so, in 1969, she quit. Abruptly and totally. She destroyed almost all of her commercial negatives; her more artful editorial negatives were stuffed in a couple of trash bags and jammed in a basement storage closet.

She forgot about the negatives; the fashion world forgot about her, and Bassman turned her artistic talents to other venues. She only photographed the things she wanted to photograph; she did a series on cracks in sidewalks, she photographed distorted images of fruit and vegetables, she rephotographed pictures of male bodybuilders reflected in mylar sheets. Her husband Paul, who’d also grown cynical about commercial photography, supported them by becoming a psychiatric social worker.

Likely they would have happily lived out their lives that way. But in the early 1990s, Martin Harrison, an art curator and historian from London, was visiting Bassman and her husband – and he found the trashbags of negatives. He encouraged her to revisit the photos. She was initially reluctant – then “I got a little intrigued, and I took them into the darkroom, and I started to do my own thing on them.” She applied some of the darkroom techniques she’d first learned in the 1940s.

Harrison arranged a show of her work, and suddenly Bassman was back at the center of the fashion world. She was hired by Neiman Marcus to shoot an advertising campaign, the New York Times Magazine hired her to shoot the couture collections in Paris, and at the age of 80 Lillian Bassman became the hot new thing. She quickly embraced digital photography when it became practical, and when she was 87 years old she learned to use Photoshop.

Lillian Bassman continued to work occasionally as a photographer and Photoshop artist until February 13th of this year, when she died. She was 94 years old.

In the late 1940s, not long after she’d left Junior Bazaar and became an independent photographer, Bassman was hired by her old employer, Harper’s, to go to Paris and shoot the fall couture collection – just as Richard Avedon had done when he allowed her to use his darkroom. When Carmel Snow, the ferocious editor at Harper’s saw the first prints of Bassman’s photographs – images of a model at twilight on a hotel balcony, wrapped in chiffon and moonlight – she said “I didn’t bring you to Paris to make art; I brought you here to do the buttons and bows.” So she gave them buttons and bows. But a few years later, even the notoriously hard-to-please Mrs. Snow would acknowledge that Lillian Bassman could take the most awkward design and find a way to make it look elegant.

“There’s something in me that finds within the worst [fashion] something that gives the body some allure. Some way of moving. Some way of shifting the shoulder…. It’s a real undying love of fashion that shows through everything I’ve tried to do, and the way the body moves within the fashion.”

If there’s a metaphor for the life of Lillian Bassman, I think we can find it that comment. She found a way of moving through life, a way of shifting the shoulder that allowed her to reveal the elegance and grace she experienced in the world around her.