I’ve been coming across the name Jason Eskenazi for two or three years now. It’s an easily remembered name. I’ve seen it pop up on the periphery of a conversation about street photography, I’ve heard it mentioned with respect by photographers I trust, I’ve seen the name come up in a few photo blogs and at least a couple of times in magazines. After a while I started thinking “I’ve got to check out this Eskenazi guy.” But for some reason, I never followed through.

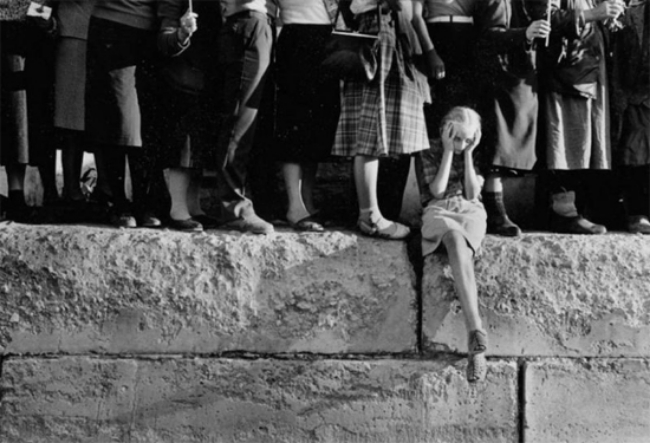

A few months ago, completely by accident, I saw the following photograph. It’s such a wonderful photo on so many levels; I was immediately taken with it. Then I noticed it was by this Jason Eskanazi guy. And that was it…that was the spark I needed to seek out more of his work, and after just a few minutes I discovered two things. First, Eskanazi is a wonderfully skilled and intuitive photographer. Second, I’d been a total putz for not tracking him down earlier.

Eskenazi, born in Queens, New York in 1960, traces his interest in photography back to 1968. “I was eight years old at my brother’s Bar Mitzvah. I would follow the photographer around like an assistant. I didn’t photograph. I was just fascinated by the photographer and what he did.” It took Eskenazi another eight years to acquire an actual camera; when he was 16, his father bought him a 35mm Cavalier – an inexpensive Pentax knock-off. But that was all it took.

“I’m naturally shy, as a lot of photographers are. Photography was a way for me to get out, contact and connect with people.”

Eskenazi photographed his fellow students for the Queens High School yearbook. He became the photo editor for the Queens College yearbook. He worked as a free-lance photographer for the Queens Tribune. He served as a photo assistant for other photographers. “I was just lugging equipment and changing light bulbs for color temperature and being a Polaroid stand-in for an interior design photographer.”

It may not have been exactly what Eskenazi wanted to do, but it was apparently close enough. The real problem was that he wasn’t doing it where he wanted to do it. He kept telling himself ‘I have to get out of Queens.’ He saved his money to finance his escape, but for some reason he never seemed to gather the impetus to actually pack and go.

In 1990 Jason Eskenazi was thirty years old; he was still banging out a living in the New York City photography community, still living in Queens, still hoping something extraordinary would happen. And hey, it did.

The Berlin Wall came down.

“I couldn’t sit still anymore,” Eskenazi said. “I thought, ‘I have to go out and take photos of world events to show people what was happening.’ I wanted to see what the Berlin Wall looked like. I wanted to see things for myself.“

He bought himself a ticket to Berlin, bought a many-pocketed photographer’s jacket he hoped might make him look like Robert Capa, bought a whole bunch of Tri-X film. He packed his Nikon F3 and his Leica M6 and set out for Berlin, apparently without any sort of plan whatsoever. “My plan was to just walk the wall…to be there…to be close to where history was unfolding.”

Even at 30, Eskenazi had a very romanticized notion of photojournalism. His initial exposure to the real thing did little to dispel that notion. After Berlin, he followed other photojournalists to Bucharest, Romania where he saw one of the Turnley brothers (Peter and David, well-known American photojournalist twins) standing on the back of a truck shooting photos of demonstrators. “The sun was going through his hair and he looked like an angel in command of the scene.” Eskenazi didn’t know who Turnley was…didn’t know there was more than one of them. All he knew was that something beautiful and amazing was taking place, and he was there, being a part of it, shooting photos just like the angel on the back of that truck.

Somehow Eskanazi hooked up with other photojournalists, and they began following the shifting tide of democracy in Eastern Europe. He made some connections, began selling a few photographs, took a few assignments, and after a few years of this he began to realize photojournalism wasn’t what he really wanted to do.

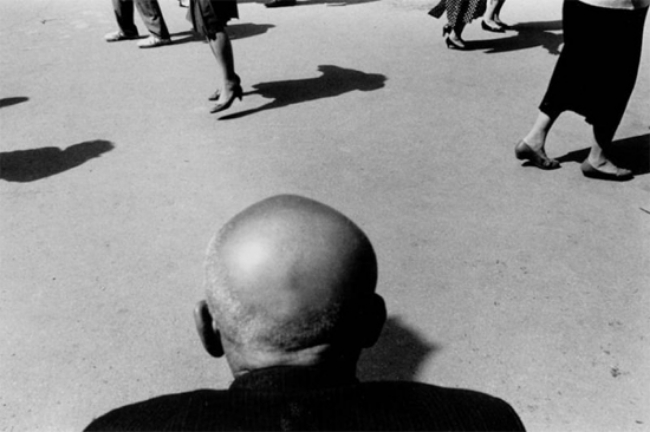

“I started to figure out that I was less interested in the direct information of events and started to take a step back. Instead of photographing someone suffering, I would step back and include someone looking at the suffering, and then I would take another step back and include myself somehow in the frame. Not literally, but emotionally.”

That realization, it seems, sparked the end of his budding career as a photojournalist. Happily, it also sparked the beginning of his career as a fine arts street photographer. From what I’ve seen of his work, I’d suggest there was always a deep element of the street in his photography. Both photojournalism and street photography require a certain emotional detachment, and both try to catch a unique human moment, but street work is often tinged with a sort of self-aware irony that is (and has to be) absent in documentary photography. Photojournalism is about bringing those moments to the masses; street photography is about an inherently personal vision.

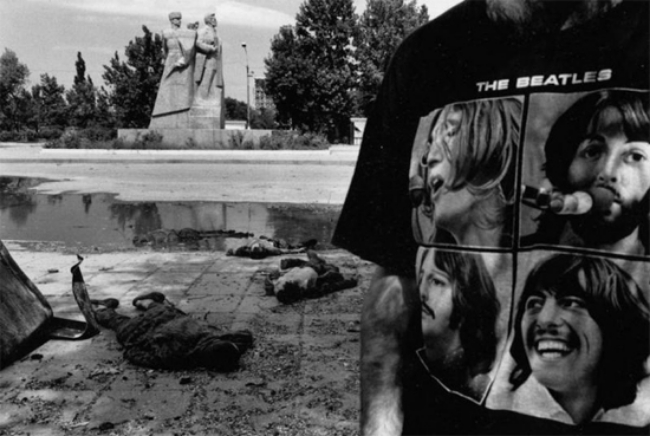

Eskenazi found himself in Moscow during the collapse of the Soviet Union and became fascinated by the Russian people. He was shooting lots of photographs, but not with any sort of project in mind. He was, in effect, just ‘walking the Wall’ again, shooting whatever intrigued him. Those Russian photographs were the start of what would eventually become his first book: Wonderland.

Why Wonderland? It’s not a term most people would apply to Russia, especially during a period of political, economic, and social collapse. But for Eskenazi there was something both magical and tragic about what was taking place around him. There was, he thought, an element of fairy tale about it. Fairy tales, he says, “are mostly about maturation, about growing up.” They’re about innocents going out into the world and encountering strangeness and mystery, encountering the unknown. He saw some parallels between classic fairy tales and the process the former Soviet Union was undergoing.

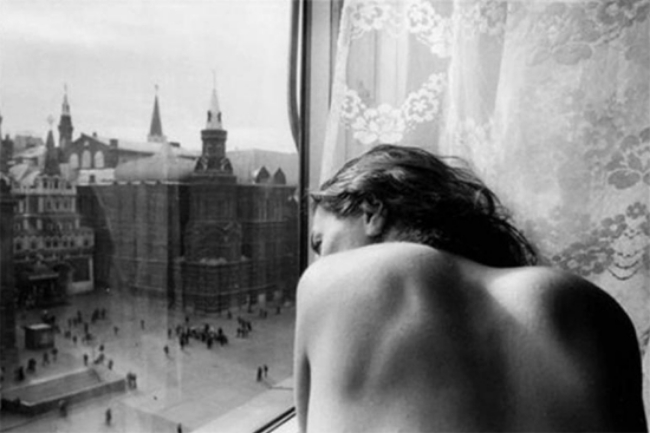

Eskanazi not only titled the book Wonderland, he structured it in a way reminiscent of a fairy tale. He decided to ignore the dates the photographs were shot and concentrated instead on sequencing a set of images. It begins with the photograph below, the putative protagonist, a young woman looking back on the old Soviet Union she’s leaving behind. However, “the pictures have no literal sequence,” Eskenazi said. “There are sequences trying to connect one image to the other image.” He would find something in the frame and use it to lead the viewer into another frame, though not necessarily the next immediate photograph. Instead, he’d insert another photo or two between the two related photographs. “I’m very conscious trying to do this; the more room you separate them, the more you leave room for the viewer to imagine something…. You want to stretch out the gap between the photos, to where there is some sort of connection, but it isn’t an obvious connection.” The result is a photography book that has an amorphous sense of flow; the eye recognizes it even when the mind doesn’t.

Wonderland was critically well-received, but like most photography books it didn’t make any real money for the photographer. Eskenazi, though, had attained enough critical recognition that he began to collect awards and grants. He was given the Alicia Patterson Foundation Grant, he earned a Guggenheim Fellowship, he won the Dorothea Lange/Paul Taylor Prize for his work in a small Jewish village in Azerbaijan, he was given a Fulbright Scholarship to return to Russia with a large format camera and shoot portraits, he was funded to organize a Kids with Cameras project to teach photography to Jewish and Arab children in Jerusalem.

In 2008, it all came to an end. Eskenazi decided he’d had enough. “For some psychological reason, I couldn’t photograph anything I didn’t really care about,” he said. “Photography was pure for me, and I couldn’t corrupt it.”

He returned to New York City, quit shooting photographs, and took a job as a security guard in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

After a period spending guarding Greek statuary in the classical antiquities section of the museum, Eskenazi asked for a transfer to the photography galleries. “The room was carpeted,” he said, “and easier to stand in.”

I rather suspect there was more to it than that. The primary exhibition at the time was Robert Frank’s The Americans. “Every photographer had the book,” he said, “but I’d never really studied [it]. So only in that exhibition was I totally enveloped inside the maze of that sequence, every single day. I got to know those photos intimately.” Eskenazi felt a deep connection to Frank. “I saw him as a poor, Jewish shlump just like myself who just wanted to make photos.“

After a large dose of Robert Frank and twenty months in security guard harness, Eskenazi was ready to pick up the camera again. He headed for Turkey, where his grandparents were born. “I was just ‘walking the wall,’ just like back in Berlin. I just went out and found interesting things.” The result of that excursion was another book, The Black Garden. His plan is to eventually finish a third book which , along with Wonderland and The Black Garden will be an exploration of different cultures as they pass through changing times, and also a very personal visual autobiography of Eskenazi and his own maturation process.

When an interviewer told Jason Eskenazi that he seemed ‘happy with the choices you’ve made,’ the photographer said, “No, not happy, there were just no other choices for me to make. I didn’t choose the path of least resistance; there was only one path for me. I always feel like I’m treading water, not swimming. I’m not happy about everything, but I don’t regret anything either. One of the earliest lessons I learned was that I wasn’t saving the world, but I was saving myself through photography. There’s no easy way out. You have to go through these things to create something honest and meaningful. Every photographer has to walk the Wall.”

Just a Jewish shlump from Queens, walking the wall, trying to create something honest. You have to respect that approach — to photography or to life.