NUDES NUDES NUDES

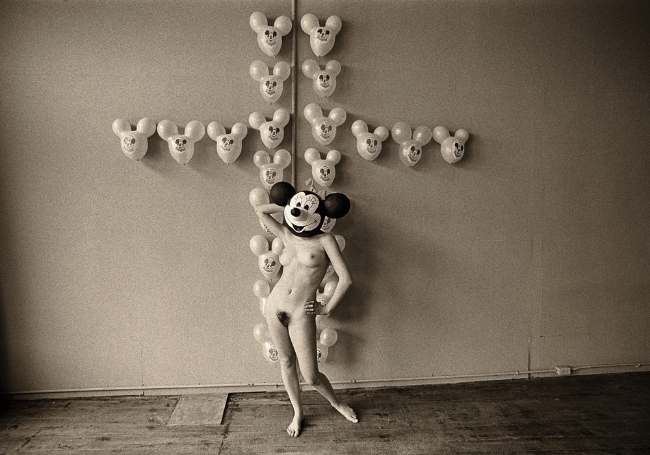

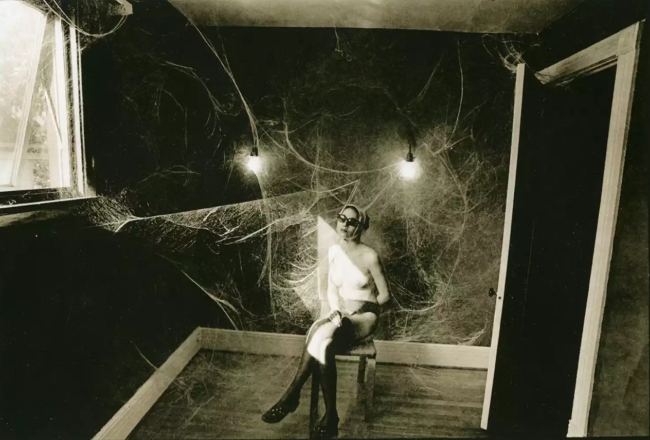

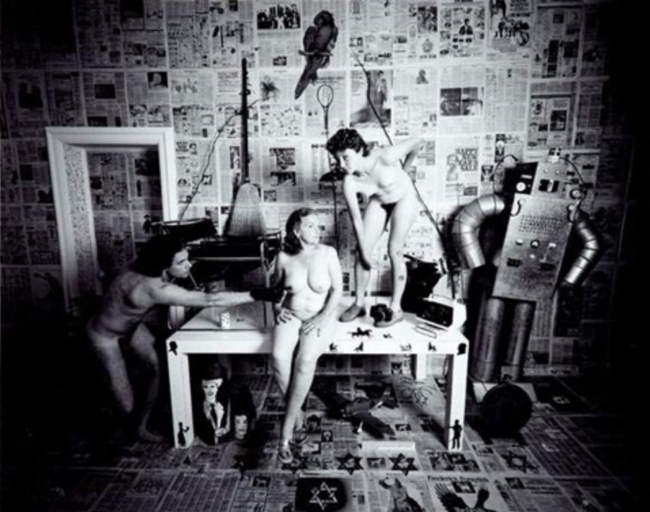

The reaction to Les Krims’ photography has generally fallen into two categories: outrage or laughter. Or both. That’s no accident. His deeply conceptual images are intentionally crafted to spark those reactions. His work has been described as provocative, misogynistic, revolutionary, racist, absurdist, and satirical. It’s certainly some of those; it might be all of those.

During the 1970s and 80s Krims created several different series that received a lot of critical attention, though very little popular interest. At a time when ‘serious’ art photography was largely focused on the immediacy of the street, Krims was creating large, highly structured and compulsively detailed photo tableaux. Krims wasn’t interested in ‘capturing’ the zeitgeist; he was interested in commenting on it.

There was very little room for spontaneity in Krims’ compositions; he included only the elements he wanted and carefully removed those elements he didn’t want. Despite the formality of that approach, Krims’ work is decidedly eccentric.

“It is possible, to create any picture one imagines.”

Krims work has been at the center of a few exceptionally bizarre incidents. In 1971, his work so offended one person in Memphis, Tennessee that it sparked a kidnapping. A young boy was abducted; the ransom for his return was the removal of Krims photographs from the gallery exhibiting them. The photos were removed and the boy was released.

The following year, 1972, Krims published a series called The Incredible Case of the Stack O’Wheat Murders. This was a series of pseudo-crime scene photographs depicting nude or semi-nude women as victims of sexualized murders. Beside each victim was a stack of pancakes. Anybody who purchased a complete set of the ten 14 x 17 prints also received enough pancake mix to make a single stack of pancakes and a can of Hershey’s syrup, which is what Krim used to simulate blood in the photos. In 1980, when the University of California at Santa Cruz was exhibiting this series, an activist named Nikki Craft saw the exhibit the day after a local woman had been raped and murdered. Craft ripped up some of the photographs and poured the Hershey’s syrup over them. (As an aside, Craft was acquitted of the charge of Malicious Mischief after she presented a defense arguing that the destruction of Krims’ photos was itself a work of performance art. Another aside…months later, Craft purchased a complete set of the Stack O’Wheat series and donated them to the university.)

Krims’ primary interest in photography appears to be as a tool by which he can offer a critique of modern society. Even so, not all of his work is outrageous or politically provocative. He has shown that he can also create works of strange, delicate beauty.

Krims was born in 1942 and raised in a two-room apartment in Bensonhurst, a working class neighborhood in Brooklyn. He was, apparently, a precocious child and was able to attend one of NYC’s specialty high schools: Stuyvesant High School, which specialized in mathematics and science. He later graduated with a Fine Arts degree from The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, which is one of the most selective colleges in the U.S. He earned a Masters in Fine Arts from the Pratt Institute, one of the leading art schools. He now teaches in the Fine Arts Department at Buffalo State College.

Although he has an academic career, Krims seems to have little regard for the role of academia in art. In fact, Krims has little regard for art photography, especially street photography. He has described art photography as “a small industry, an amalgamation of arts and government agencies, which used the poor and damaged as the raw material for a perverse entertainment.”

Krims is a rarity in the art world; he describes himself as a political conservative and he has stated he sees his work as a means of “irritating the left.” He generally believes most modern photography falls into two categories, which he calls “East Coast Lefties and West Coast Lefties.” Krims claims these photographers are “funded by liberal media or government agencies,” and suggests “these photographers helped advance Marxist cant and misinformation. They despised America and wanted this country to fail. They still do.”

Krims’ photography, ironically enough, is addressed primarily to the very people he intends to excoriate–the academics, the theoreticians, the scholars, and the abstract thinkers.

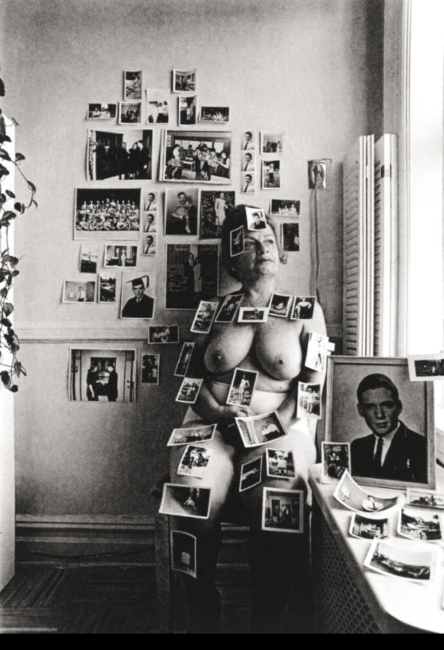

One of Krims’ most frequent nude models is his mother. He photographed her for the series Making Chicken Soup, in which she appeared dressed only in panties while she, appropriately enough, prepared chicken soup. According to Krims, the series was intended to suggest that “socially concerned photography” was like chicken soup, in that it was a palliative that might make people feel better but didn’t actually address the problem. Krims maintains that such photography is “mired in slumming excursions funded by affluent folk eager to see what danger looked like.”

I’m not quite sure how photographs of his semi-nude mother offers a critique of socially concerned photography, but clearly Krims sees a connection. He argues that in his work he attempts to “avoid the ideological constraints of the leftist traditions of America’s activist photographers.”

Les Krims exerted a significant influence on his students in Buffalo. One of those students, Cindy Sherman, has also relied on his approach of using staged scenes as a method of commenting on modern society, although she’s gained much more artistic credit and financial rewards than Krims.

The work of Les Krims, despite all the outrage and bizarre behavior it sparked among activists and intellectuals in the 1970s, never quite attained the cultural significance he hoped it would. He tends to blame this failure on “leftist controlled media” and the “academic art establishment“. He apparently sees himself as something of a martyr. In a recent discussion with an art critic Krims said, “I wouldn’t worry much about my point of view winning converts. But you should take heart that it can be expressed. We live in a free country, defended at this moment by brave soldiers, and led by George Bush.”

Regardless of the reasons for its failure, Krims work remains an expression of a unique voice. It demonstrates that a singular, idiosyncratic vision can produce works that engage the mind, even if they fail to reach a wide popular audience. One doesn’t have to agree with Krims politics or perspective to appreciate his creativity.