I’m not sure how much this influenced my take on the photography of Robert and Shana ParkeHarrison, but I first encountered their work on one of those dreary, unseasonably chilly, drizzly grey days when the sun never comes out. The Scots have a word for it: dreich; a day that’s devoid of light, color, and warmth. A day for staying inside, wearing flannel, drinking something warm (maybe with a wee tot of the hard stuff in it).

Now I tend to associate their photography with that sort of feeling–glad to be sheltered and snug inside where I can appreciate the bleak, leaden, world outside. There’s a weird sort of satisfaction in that.

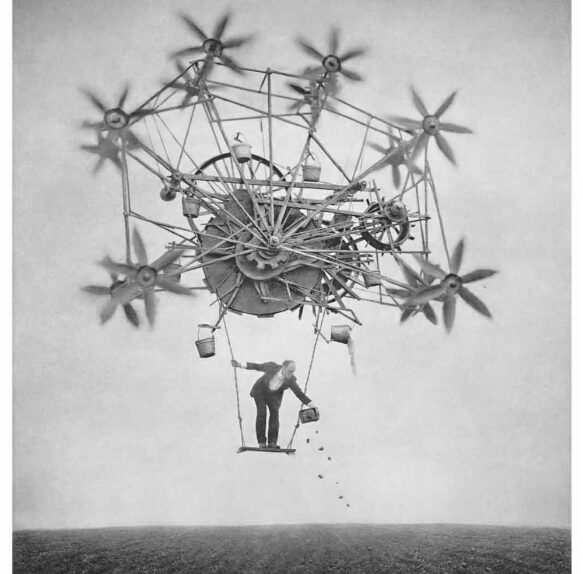

The work of the ParkeHarrisons seems to be comprised of moments in an imagined narrative. They appear to tell the story of an anonymous, black-suited civil servant who was given the thankless and impossible task of maintaining the earth’s systems: tethering the clouds to the land, insuring the wind doesn’t stop blowing, keeping the shore and the sea from parting, patching holes in the sky, repairing the rain-making equipment, managing the change in seasons, insuring that seeds get spread. The images make it clear the poor man is overwhelmed by the magnitude of the assignment, that it leaves him spent, physically and emotionally exhausted. But he keeps at it, quietly and determinedly, ritualistically, heroically, absurdly.

Robert ParkeHarrison, who teaches photography at the College of Holy Cross in Worcester, MA, said this of his work:

“I want to make images that have open, narrative qualities, enough to suggest ideas about human limits. I want there to be a combination of the past juxtaposed with the modern…. These mythic images mirror our world, where nature is domesticated, controlled, and destroyed. Through my work I explore technology and a poetry of existence. These can be very heavy, overly didactic issues to convey in art, so I choose to portray them through a more theatrically absurd approach.”

I’m a tad troubled by his references to ‘my’ work rather than ‘their’ work, but I very much like the implication that control is an illusion. Or perhaps it’s more of a delusion–an unfounded belief that nature can somehow be ‘domesticated’ or tamed. What I see in their photography is a thoughtful, sophisticated visual articulation of that concept. The arrogance and absurdity of the belief that the earth’s natural systems can be ‘managed’ doesn’t diminish the quixotic dedication of the civil servant attempting to do the managing. The guy is trying to do an impossible job while knowing it’s impossible.

These are political photographs without an overt political message. They’re art photographs in which the art is hidden. They’re landscape photographs in which the landscape is imaginary. They’re tragic photographs in which the tragedy is masked by the absurdity. They’re portraits in which the subject is Duty.

And that sort of brings me back to the beginning of this salon. While this anonymous person is out there busting his ass in an attempt to reach an unreasonable and unattainable goal, the viewer gets to stay inside where it’s comfortable and amiable. Robert and Shana ParkeHarrison aren’t offering any solutions; they’re simply trying to get the viewer–to get us–to think about what we’re asking others to do and maybe ask ourselves if there’s a better way.