Bruce Gilden offends me. His photographs offend me. His approach to photography offends me. Even his success as a photographer offends me.

I like that about Bruce Gilden. I’m actually glad he’s out there offending me. I think it’s important for the craft and art of photography that photographers like Gilden exist. I’ll come back to that in a bit – but first let’s try to understand how and why Bruce Gilden became Bruce Gilden.

He was born in Brooklyn in 1946. Brooklyn in the 1940s was largely a white ethnic borough: first and second generation immigrants – Italians, Irish, Eastern European Jews, Ukrainians, Poles. This was the era that gave birth to the stereotypical ‘guy from Brooklyn’ so often seen in the movies – a brash, tough, street-wise smart-ass who said things like “Yeah, my fadda said he’d moidah me if I joined da ahmy.” That stereotype turned Brooklyn into something of a national joke. It was a borough of underdogs – and sometimes resentful underdogs – and that surely helped shape the way Gilden saw the world.

He has described his childhood family as “a total mess”. Gilden says, “Emotionally I was beaten up as a kid. I had a tough upbringing…. I have that inside of me. You know, that anger. That I’ll always have.” The centrality of that anger can be seen in the way Gilden talks about his photography. “My pictures are me. Whatever I take a picture of, it’s me. It’s about how I feel and I don’t have to think about it.”

His childhood may have been rough, but Gilden was able to get into Penn State University, where he studied sociology. At some point he saw the Michelangelo Antonioni film Blow-Up, about a London fashion photographer who accidentally photographs a murder. That was apparently enough for Gilden to decide he wanted to be a photographer. In 1968 Gilden was 22 years old and back in New York. He bought an inexpensive Miranda camera and began taking evening classes at the School of Visual Arts.

At that time, most street photography fell into two different approaches. There was the Cartier-Bresson approach – the photographer as ninja, moving gracefully and invisible, silently catching intimate but decisive moments. And there was the Garry Winogrand approach – a more New York City style, open and direct and overt. Where HC-B was a ghost, Winogrand was as obvious as a sore thumb. He just didn’t care if his subjects saw him taking their photograph. In fact, in many of Winogrand’s best photographs the subjects are looking directly at the photographer.

Gilden, the Brooklyn boy, took the Winogrand approach. Took it and eventually pushed it as far as it was possible to go.

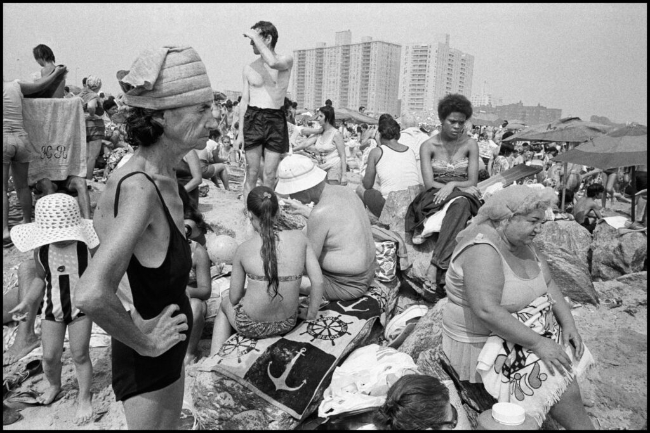

Gilden’s first major project was sort of classically Winograndian; he photographed people at Coney Island, just a subway ride away. He spent a couple of decades shooting the Coney Island beaches, mostly the sections where the old and poor gathered to enjoy the sun and the waves. Even in the earlier images, you can see where Gilden began to expand the Winogrand universe.

Gilden got close to most of his subjects, using a wide angle lens, and often filling the entire frame with something for the eye to see. He started getting even closer than Winogrand would. Uncomfortably, intrusively, compulsively close.

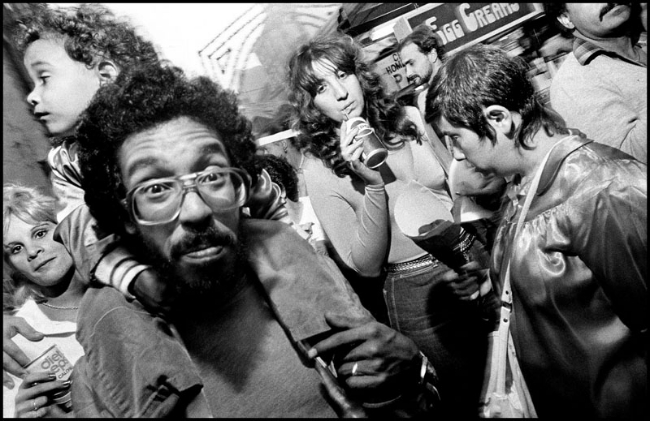

This is the beginning of the Bruce Gilden we all know and…well, love or hate. Moving from the beach to the street, Gilden created his signature style. “My style evolved because I liked being among the common man,” Gilden has said. “I like characters. I always have. When I was five, I liked the ugliest wrestler, so it was easy for me to pick what I wanted to photograph.”

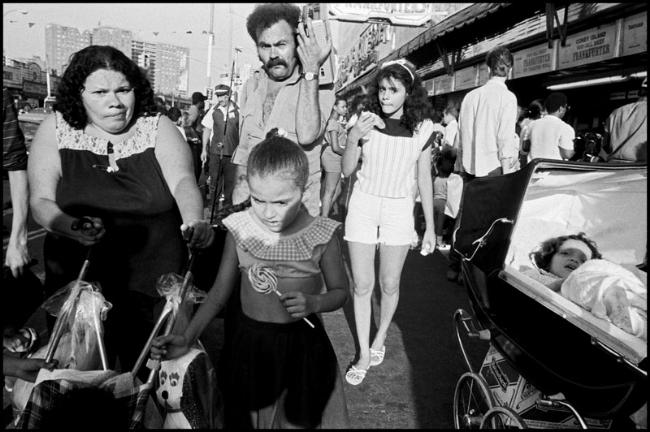

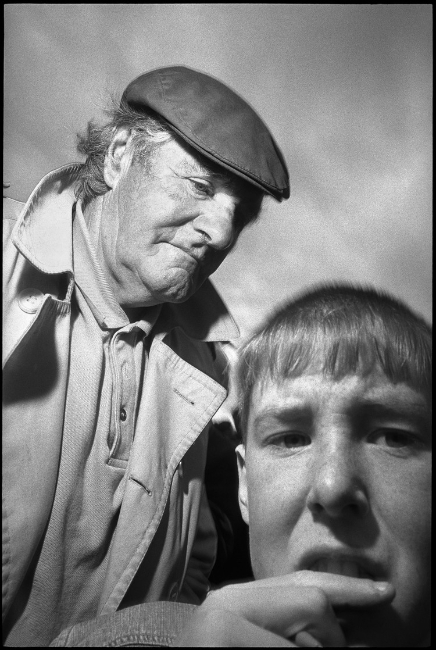

Gilden’s street photos – the work that made him famous (or notorious) – grew out of his Coney Island experience. It’s an aggressive, sometimes confrontational, style of street portraiture. Videos of Gilden at work (and there are a lot of them available on YouTube) show him walking the streets looking for ‘characters’ – people who attract his attention for some reason. Maybe it’s a physical feature, maybe a style of dress, maybe the way they move. When he spots a ‘character’ he gets close, steps in front of the person, and with his camera in one hand and an old Vivitar flash in the other, he snaps a photo. In effect, this is photography by ambush.

Everything about this approach is intrusive. The subject is surprised, often startled or alarmed, sometimes angry. That spontaneous emotion is what drives Gilden’s work. When I say he gets close, I mean really close. He usually shoots with a 28mm wide angle lens, often at a distance of an arm’s length or less. He generally squats a bit, giving the image an upward angle that tends to exaggerate the facial contortions of many of his subjects. The flash effect adds to the overall grotesquerie.

The effect is startling. And raw. And powerful.

“[S]ince I work in a spontaneous way, I have to be a little bit sneaky because I don’t want them to know that I’m going to take a picture of them.” The ethics and morality of that approach (or the lack of ethics/morality) offends and outrages a lot of people. Gilden doesn’t care. He’s shooting the photographs he wants to shoot, and he’s getting the results he wants.

What I found most surprising, though, is that when you listen to Gilden talk about the people he photographs – not about his approach, but about the actual subjects – there’s a very obvious affection for them. “All these people I photograph, they’re like my friends…. I was drawn to them somehow.” These are Gilden’s people – the anxious, the distracted, the frustrated, the unusual, the uncertain, the damaged. “There are a lot of things wrong with this world, and I feel that, so that’s what my pictures are about. I always liked the underdog—the guy who’s not the average person—and I see a lot of pathos out there.”

Gilden has, of course, a broader body of work. He’s not just a New York street photographer. He’s worked in Ireland, Portugal, India, Japan. He’s probably spent more time photographing Haiti than any traditional documentary photographer. He did a wonderful series of landscapes of foreclosed properties. Gilden has even done a series on state fair food.

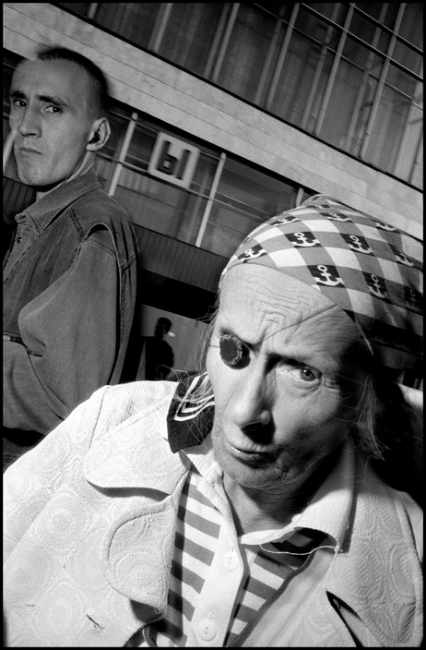

He’s largely moved on from his street ambush work. Part of that decision was based on age. “I’m old. I mean, I function well, but I changed. I started to do the portraits, because I can’t beat up my legs.” All that squatting takes its toll on the knees. Now he’s focusing more on actual portraiture – though with a Gildenesque twist. He’s still working incredibly close, he’s still concentrating on ‘characters’, and he still tends to emphasize the grotesque. This IS Bruce Gilden, after all.

In the end, I’d say Gilden is a realist. He’s said there are no geniuses in photography; there are just people with talent and people without talent. He’s got a solid grasp on his place in the photographic firmament. “How many good pictures does anyone have? Maybe about twenty, twenty-five over forty-some years. I mean you don’t have a lot.”

At the beginning of this salon I said Gilden offends me, but that I’m glad he’s out there making his photographs. I said I thought Gilden was important for the craft and art of photography. Here’s why I say that.

Gilden’s work expands the range of the possible. In just about every creative human endeavor, it’s the deviants who drive change. Civil rights expanded because there were deviants who broke the law. Science expanded because there were deviants who refused to abide by the constraints of religion. Art expanded because there were deviants who ignored the rules of perspective, who splashed paint wildly and randomly, who ignored oils and watercolors and used spray paints on subway cars and alleyway walls.

By pushing at the extreme edges of photography, Bruce Gilden broadens the center. That’s where the vast majority of us work. Very few of us will ever attempt to emulate Gilden (and let’s face it, very few of us would want to), but his existence emboldens us just a wee bit. He relaxes the scope of what’s possible, and encourages us to at least think about the limits of what’s acceptable. He may offend us, but he also opens up new arenas of creativity. Bruce Gilden’s extremism protects our more modest creative steps.

Even though that’s true, I suspect Gilden would call bullshit on it.